WISERD Education Director, Professor Sally Power, explores the situation in this blog post.

While there have been growing concerns about the permeation of business in education, relatively little attention has been paid to how schools are increasingly engaged in the “business” of fundraising for charities.

At WISERD Education, we have been examining the increasingly close relationship between young people, their schools and charities. Our research, based on surveys of over 1,000 school students in Wales, shows that young people have a high degree of engagement with charities, and that schools play a significant part in this.

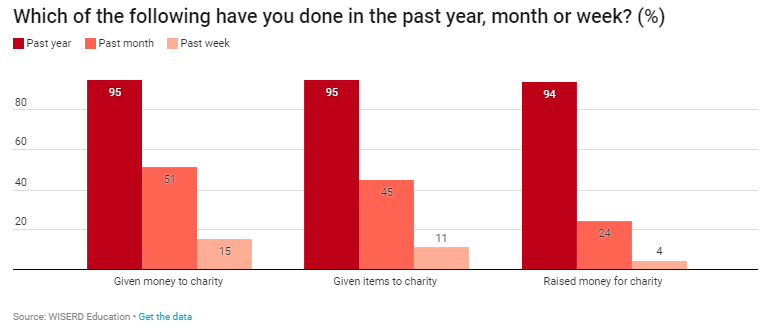

We found that the overwhelming majority of the students — age 14 to 18 — had been actively involved in not only donating money and goods, but also fundraising for charities. The chart below shows that in 2016, nearly 95% were involved in fundraising in the preceding 12 months. In addition, nearly one quarter (24%) had fundraised in the month before the survey was taken.

We also asked the students to name the last charity their secondary school had supported. They identified 37 different charities, the top ten of which were Children in Need, Cancer Research UK, Sport Relief, Wales Air Ambulance, Catholic Agency For Overseas Development (CAFOD), British Heart Foundation, Text Santa, PATCH (a local foodbank and clothing charity), Macmillan Cancer Support, and Tŷ Hafan (paediatric palliative care).

Research shows that it is almost certainly the case that the pupils’ schools play a big role in fostering these activities. A 2013 Charities Aid Foundation survey reported that, after television, young people were most likely to find out about charities through school. Another study, by education marketing company JEM, showed that the average secondary school donated nearly £7,000 to charity in 2012-13. Indeed, just over half of the secondary schools in that study had a designated school-wide charity coordinator.

Engagement and responsibility

There are likely many positive aspects to the promotion of charities in schools. It can be argued that charitable activities are important to develop a sense of citizenship — in terms of individual engagement, participation in collective school activities, and engendering a broader sense of social responsibility.

Nearly all the charities listed above have dedicated resources for teachers, to help them organise communal fundraising events within their schools. Children in Need, the most frequently mentioned school-supported charity, provides a range of materials for school activities such as cake stalls, art projects and discos. It might be argued that the educational benefits of these kinds of activities are not self-evident. But it can also be said that they bring a sense of common purpose, and help build a strong school ethos.

But the mainstreaming of charities may not always have such benign consequences. Concerns have been raised about the promotional activities of charities in general. And some of these now need to be voiced in relation to their permeation in schools in particular.

Business links

In addition to worries that some bigger charities are essentially little different from business, almost all of the charities that our schools supported have visible links with businesses. Children in Need is heavily sponsored by Lloyds Bank, and supermarket chain ASDA is also actively involved in directly marketing its products to school children within fundraising materials. Sport Relief, the third most frequently mentioned charity, also has business partners, including Sainsbury’s, BT, British Airways and Amazon. The logos and links to these companies feature in nearly all the promotional resources for schools.

There are also questions about the extent to which presenting charities as the “solution” to a range of social “ills” downplays the potential of other approaches. Many of the problems tackled by the charities our respondents supported — child poverty, homelessness, animal welfare — could perhaps be more appropriately addressed through government solutions. By continuing to provide “sticking plaster” remedies for chronic social needs, charities might serve to maintain the conditions that create the problem and forestall the more fundamental changes needed.

Evidently, though there are many potential benefits to charitable engagement in schools, there are still deeply concerning issues to address. Is the mainstreaming of charities evidence of increasing commercialisation within schools? Set within a political climate where civil society is increasingly being heralded as the answer to a wide range of enduring social and economic problems, it’s open to question whether schools should be endorsing the virtues of charities when state interventions may be more appropriate.![]()

There are no straightforward answers. But rather than assuming that any kind of charity engagement within schools is unquestionably worthwhile, schools and their students at least need to consider these questions.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Click here to read the original article.