In 1979 at a time of great social and political change I was living in Durham. I was closely involved with the coal miners and the NUM, and also with a group called “Strong Words” that we had set up to record and publish the words and images of working-class people in the North East of England.

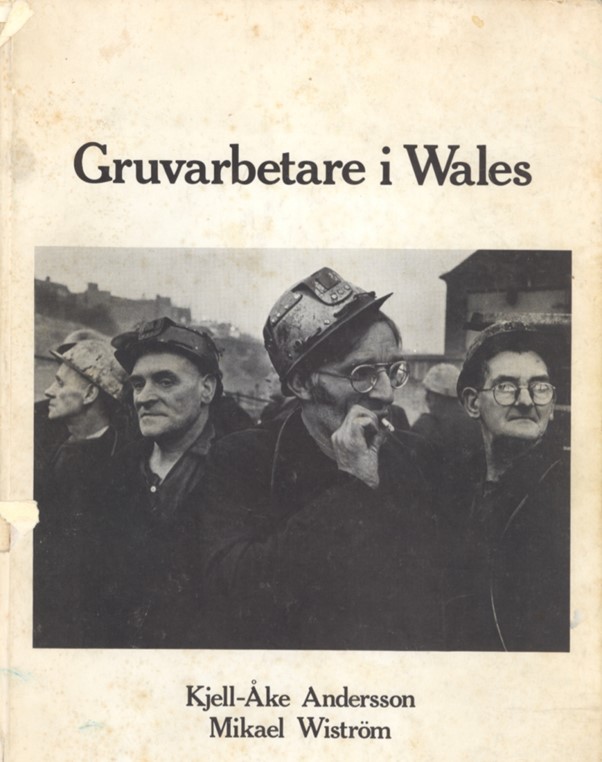

We organised many public events and exhibitions of words and photographs and we had many visitors. One of them, Rai Paul, was from Sweden and gave me a book that he thought fitted well with the work we were doing. It was called Gruvarbetare I Wales (Miners in Wales) and was a collection of photographs by Kjell-Ake Andersson of miners at the Bargoed colliery in South Wales. I was stunned by it: by the images of the miners and their families, by the ever-present coal mine and the dust and the blackness. It has stayed with me ever since, and my recent book (with Ray Hudson) The Shadow of the Mine begins with an image of Bargoed colliery taken from that book.

Andersson had visited South Wales in 1973. At that time, he was a student at the photography school in Stockholm and was on an expedition following in the steps of Eugene Smith, the American photographer who had seen in the mining villages of south Wales classic images of labour under industrial capitalism. Here too they had seen the strength of community life that had come to underpin trade unionism and social democratic politics in Britain. Smith was in fact one of Kjell-Ake’s role models and, as he explains:

In 1950 he was in Wales photographing mining communities. I fantasized about going there because I thought it looked like when Smith was there in the 50s. This was in the autumn of 1973. Me and my wife and our 7-month-old baby took our old car and took the ferry to Britain.

As others had found in the fifties, there were few places for visitors to stay in the mining villages. In Bargoed, the little group had thought that they might stay in the local pub. However, the miners felt that this would be inappropriate and inhospitable, with one offering them a room in his house instead. Which is where they stayed and became widely accepted by the miners and their families.

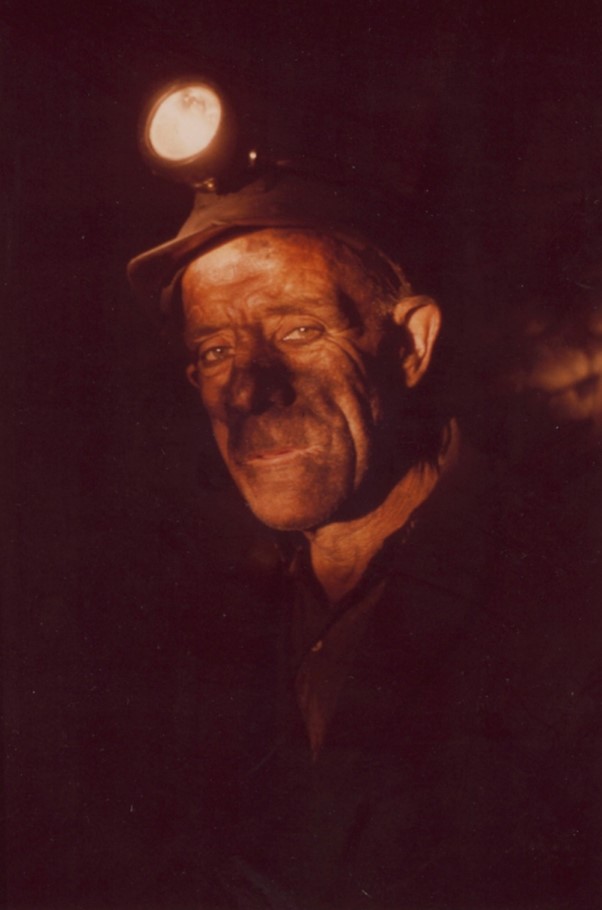

But it was hard work. It began with the miners’ morning shift when Kjell-Ake would stand with his camera day after day taking photographs until he became part of the landscape, blended in, and accepted as a new part of village life. Over time the people of Bargoed become involved in the project. It was the miners who insisted that Kjell-Ake had to join them with his camera underground, saying that the project would be incomplete without photographs of where the work actually took place. The opposition of colliery management had to be overcome! This took time and much coming and going between Bargoed and Stockholm, but in 1976 he finally got permission from the NCB to photograph the miners underground. It was this level of community engagement that made the book one of the most perceptive visual accounts of mining life during a critical period.

In 1973, the people in Bargoed remembered that, in the previous year, they had been involved in a victorious national strike. Following a decade of colliery closures and changes that had eroded miners’ wages they demanded recompense and a Court of Inquiry under Lord Wilberforce had supported their case reporting that:

Working conditions in the coal mines are certainly amongst the toughest and least attractive and we agree that miners’ pay levels should recognise this. Other occupations have their dangers and inconveniences, but we know of none in which there is such a combination of danger, health hazard, discomfort in working conditions, social inconvenience and community isolation.

These conditions endured after the strike had ended. They are captured in Andersson’s photographs taken on the surface of the mine, in the lamp room and the bath house, and also underground in the roadways and at the coal face. Here, at a time when the National Coal Board had still not issued overalls to its workers, we witness the ingrained dust and dirt of the mine on the clothing, faces and bodies of the miners.

We see the activity of the mine, the bending, crawling, shovelling, and carrying. Through careful portraiture we get a glimpse of the character and camaraderie of working together underground, of being together in the cage and, thankfully, ending the shift. On the surface too the photographs taken in family homes and in the clubs have a natural feel. Together they create an atmosphere of community, located within a stark and physically isolated environment. The trade union is present too with lodge meetings led by the lodge secretary Elwyn Andrews and the lodge banners that came together during the national strike in 1974: a short strike that provoked a general election and the end of the Heath government. Momentous times.

In 1985, Kjell-Ake returned to South Wales, this time as a film director to record the miners who were involved in the longest strike in the history of British coal mining, attempting to stop the closure of the mines. As he explains,

I went there because I was so angry and irritated by the reporting of the strike in newspapers and on TV. No one described Thatcher’s attacks on the trade unions and the working class. I wanted to show the reason why the workers went on strike.

In 1977, Bargoed had joined the long list of closed collieries, so a new site was needed. In the Eastern valleys Oakdale colliery remained one of the area’s “big hitters” and was considered more secure than most. The men there had a reputation for moderation, but in 1984, they voted for strike action. It was here that Andersson set up camp in February to make his impressive realist documentary “Breaking Point”.

Once again his engagement with the local community is clear, giving the camera a discrete unseen presence as it joins with the people on picket lines, in canteens and mass meetings, drinking in the club and watching TV. His approach as ever involved “showing respect and being curious without disturbing anyone. A fly on the wall”. Here again he became more and more “impressed by the cohesion and strength among the miners and their wives and other women despite the strike going on for almost a year”.

With winter set in, the snow falling, and as some men start to return to the pit, we see the resilience of those who remain on strike and also the tensions that emerge within a once united community. Tensions that create problems for the local NUM lodge, and impel its chairman, Dan Canniff, to use the phrase that becomes the title of the film. With one eye on the future, when the strike will end, he urges caution over the condemnation of those have returned to work, after being on strike for eleven months. People, he says, have different circumstances, they are not all the same and all have different “breaking points”.

Here, and throughout the coalfield, the support of the women for the strike (in a variety of different ways) was critical and we see this through the lives of Cath Francis and her husband Ray. They talk about juggling domestic arrangements to accommodate Ray’s picketing and Cath’s involvement in the support group which is clearly pivotal but which nevertheless leaves her with pangs of conscience and embarrassment over domestic roles unfulfilled. The women took responsibility for preparing meals and played an important part in the door-to-door neighbourhood collections for food and other donations to the miners’ cause. We see this on the doorstep and also at the meeting of the women where some of the men “the lazy buggers” are criticised for refusing to help. It’s pointed out to applause that “the tins don’t grow in them carrier bags”. In response the chair, drawing implicitly on “heroic” and masculine images of miners, explains that while men might go picketing “when it comes to food collection and standing on street conners with the tin open asking for money…. some men have dignity”.

Everywhere there are glimpses of cracks appearing alongside strenuous efforts to hold things together. Alan Baker the lodge secretary was well known across the coalfield as an erudite and leading proponent of a broad front approach to the struggle, going beyond the mass strike to build more general support from the public though communication and alliances. We see him in conversation over strategy with Dan Canniff and at a meeting with the convenor of the local Switchgear factory to receive the regular weekly donation that has been made by the workers there throughout the strike. Most telling is the scene where he is filmed watching Arthur Scargill on television, where the NUM President uses the opportunity to speak directly to his members who are still on strike. Visibly frustrated Baker, speaking to his wife, who is off camera, he calls for a different approach one that directly involves talking to and engaging the public. We see him for the last time standing with a pint of beer, alone and disconsolate, in the club.

The strike continued as did the arguments with management. Everywhere in mining strikes (and in others too) there have been disputes over the amount of necessary work needed in order to preserve the facility of the mine. Water needed to be pumped out and where faces had been standing for many months questions emerged over strata control and the security of the machinery. This became an issue at Oakdale and the lodge officials needed to be convinced that it was not a con but a real threat to the future of the mine. A threat to their future. The tension over sustaining the strike and securing the mine was clear. The dilemma that eventually resolved through an agreed and partial return to work. Here the film ends and with it a sense that the strike itself had run its course and would soon end.

The film Breaking Point and a collection of the Bargoed photographs will be shown in Cardiff at a conference on 2 March 2024 – The past in the present: Reflections on coal mining and the miners’ strike 1984-85.

This post was originally published on huwbeynon.com.

Image credit: Kjell-Ake Andersson