Our previous blog showed the challenge facing British democracy stemming from the sharp age-based differences in electoral turnout: while younger people have always been less likely to vote, since 1970 the difference between them and their elders has trebled. Since 2001, it has been fair to say that the average British young person does not vote.

It is not only the difference between young people and their elders that poses a challenge to the representativeness and vibrancy of British democracy, however – there are important and just as serious gaps between the turnout of young people from different backgrounds as well. One of the most substantial divides is between those who go to university and those who do not. While getting a degree is not nearly as beneficial as forty years ago for a person’s employment prospects or financial security, it remains extremely valuable for their political engagement, providing them with skills, information and networks that make them more likely to be interested in politics and to vote. Students can, for example, get experience of politics and elections by taking part in students’ unions or associations; they can develop extensive social networks that provide information and support for engaging with political campaigns and debates; they can develop skills that make participating in the politics of their communities off campus easier (such as public speaking or engaging in collective action); and they can be taught about how politics and government works, or exposed to debates that stimulate a lasting interest in political affairs. Universities can also be sites of political mobilisation: one of the most effective ways of getting someone to vote in an election is asking them to do it, and it is far easier for political candidates and campaigners to find young people and encourage them to vote on university campuses than in the wider community or workplace.

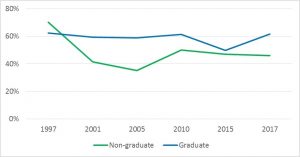

By contrast, young people who don’t go to university are much less likely to receive such benefits. Instead, they are likely to enter a difficult labour market, where opportunities for low skilled yet secure and well-paid employment are few. While some may be supported to engage with politics by their parents, neighbours or (if there is one in their workplace) a trade union, their economic precarity means they have many other things to worry about (like paying the rent and putting food on the table) that leave less room for politics. It’s unsurprising, therefore, that the decline of youth turnout in Britain has been more pronounced amongst those who did go to university, as Figure One illustrates. While in 1997, young non-graduates were actually slightly more likely to vote than, since 2001, the turnout of non-graduates under-30 has been 14% lower on average than that of graduates. In the 2017 election, 62% of under-30s who had some form of higher education qualification voted, compared with just 38% for those who did not stay in school past age 16.

Figure One: Under-30 Turnout in UK General Elections since 1997: Graduates vs. Non-Graduates

Source: British Election Study

The turnout inequalities within today’s young generation are just as important to address as those between young people and their elders. Not only is it important that all citizens are given the same opportunities to take part in politics and societal decision-making, but we need our politicians and elections to be representative of the views of all groups in the electorate. Taking the example of Brexit, it is well known that the vast majority of young people supported remaining in the European Union in the 2016 referendum. WISERD’s research also showed, however, that among those young people who did not vote, there was much more support for leaving the EU. These pro-Brexit young people receive virtually no attention in public or media debates.

The introductory blog of ‘Social Action as a Route to the Ballot Box’ outlined how volunteering could help reduce the turnout gap between young people and their elders in UK elections. A potentially more powerful benefit could be that it could reduce the gap between young people who did and did not go to university, by giving the former opportunities to develop skills and interact with their communities that they may otherwise not receive, and so help them become more engaged with politics. This is why the potential for volunteering and schemes that promote it to address not only inequalities in turnout between young and old, but between young people from different social backgrounds, is a further key research objective of ‘Social Action as a Route to the Ballot Box’.