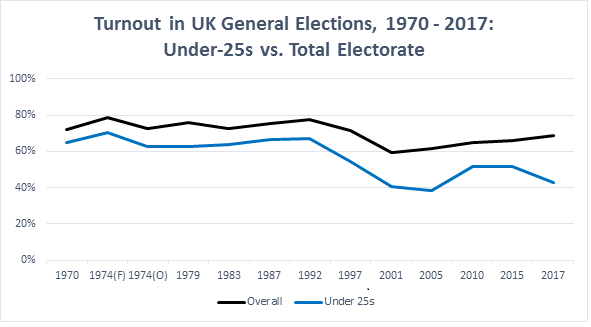

In the 1970 General Election (the first following the reduction of the voting age to 18), 65% of eligible 18-24 year olds voted – roughly 7% lower than the turnout for the whole electorate. By the 2017 election (despite claims of a so-called ‘youthquake’), this difference had trebled: fewer than half of eligible 18-24 year olds voted. Since the late 1990s, young people have been far less likely to vote than their parents or grandparents when they were a similar age; youth turnout has fallen to such an extent than the average British 18-24 year old no longer votes in elections.

The problems arising from this age divide are both short and long-term. Young people are under-represented in societal decision-making, such as about which party should form a government, or Brexit. They are also disadvantaged in policy-making, as politicians have a far greater incentive to prioritise older, more politically active citizens, as the Liberal Democrats’ notorious decision to support a trebling of university tuition fees while pensions were increased following the financial crisis illustrates. The long-term problems are potentially even more serious, because voting is habitual: people who get into the habit of voting while young are likely to continue doing so for the rest of their lives; people who get into a habit of non-voting are likely never to vote. If the low turnout of today’s young people becomes a lifelong habit, therefore, we could well see overall turnout decline notably in future once more politically active older citizens have passed away. Questions about the legitimacy and representativeness of election results could follow, as well as the capacity of politicians to represent citizens’ interests and preferences being undermined. This is why finding ways of getting more young people to vote is (or at least should be) a key priority for academics and politicians alike.

While the declining tendency of young people to vote is accompanied by a decline in some other forms of electoral and non-electoral activity (such as protesting or joining community associations), there are some areas that buck the trend: most notably, volunteering. Today’s young people are just as likely as the over-25s to join organisations that promote or organise volunteering, and the 2016 Understanding Society survey showed that 25% of under-25s reported volunteering in some way in the previous twelve months compared with 21% of the over-25s. This is encouraging and offers a potential tool to help engage more young people with electoral politics, because volunteering (like many other forms of community activity) can act as a ‘gateway’ to electoral participation. Through volunteering, people can gain access to social networks through which they receive information that make it easier and more appealing for them to engage with elections. They can also be mobilised and encouraged to vote by these new friends; they can develop a stronger sense of civic pride that often encourages voting; and they can develop skills that make engaging with politics easier (such as public speaking, working with and debating with others, or conducting research).

While there has been plenty of research into the benefits of volunteering for volunteers and their community, and into falling turnout, there has yet to be a detailed study of whether the potential for volunteering to increase turnout – especially amongst the young – has been realised. We know little about whether young people who volunteer become more likely to vote as a result, whether they are more likely to volunteer because they are politically engaged enough to vote, or whether they have some other trait that makes them both more likely to volunteer and vote (such as a degree). We also do not know whether volunteering can help address inequalities in turnout between young people. Under-25s who went to university, for instance, are far more likely to vote (and volunteer) than those who did not. There is a clear potential for volunteering to help non-graduates in particular gain political skills and information that their counterparts may access through university, and so close this gap as well as that between young people and their elders.

This project will provide some much needed evidence to help answer these questions and see just how volunteering can be used to increase youth turnout. Working with the UK Household Longitudinal Study (also known as Understanding Society), as well as stakeholders from government and the third sector, it will examine how, through volunteering, young people can be provided with resources and information that help and encourage them to vote. The conclusions will not only help us better understand how volunteering can make young people from a range of educational, economic and ethnic minority backgrounds more likely to vote, but also inform the development of a series of proposals for the Westminster, Welsh and Scottish Governments about how their support for volunteering (such as through the National Citizen Service or Wales Council for Voluntary Associations) can be used to reduce the turnout gap between young people and their elders in elections.

The progress and findings of this research will be regularly updated on this page, and you can also keep up with them by following @WISERDNews & @stuarte5933 on Twitter or through the #Volunteering&Voting hashtag. We are also keen to work with anybody interested in this research, or in being involved with the development of policy recommendations. If you’d like more information or would like to get involved, please contact Stuart Fox, either through email or on 02920 870 984.