Cardiff is working to become recognised as a Child Friendly City. This blog looks at how the initiative has been implemented in Finland and how that experience could inform Cardiff city council’s work in this area.

The UNICEF initiative was launched in 1996 with the overarching goal to ensure the rights of the child are taken into consideration in local decision making. Examples from Finland show what this broad goal might look like in practice and what challenges the journey may bring.

There is a saying in Finland: ‘it is like winning the lottery to be born in Finland’. Growing up in the suburbs of Helsinki, the capital, I can confirm that, as a child in the 90’s, it was safe to walk to school or use public transport on your own at a young age. You could play outside unsupervised and there was enough space to do so – at least in my suburb. I did not attend forest school but was able to benefit from a range of local services such as basic and further education, a library and a youth centre all within a 30-minute walk from home. Yet perhaps surprisingly, Helsinki has only recently applied for the Child Friendly Municipality status.

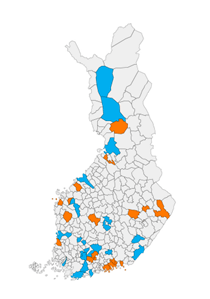

In January 2019, 19 Finnish municipalities were participating in the initiative with 13 having been recognised as child-friendly:

Figure 1 New and existing Child-Friendly Municipalities in Finland (The municipalities that had obtained child-friendly status 2012-2019 are marked in blue. The municipalities that have started the process in 2020 are marked in orange).

The Child Friendly City initiative has been active in Finland since 2012 and adapted to suit the Finnish municipal system. The suitability for municipality level was piloted in Hämeenlinna, a small city in Southern Finland [https://childfriendlycities.org/finland/]. While cities in Finland tend to be smaller the further north one travels, all Finnish cities apart from the capital region are less populated than Cardiff.

A review of reports from Finland shows that overall, the initiative has been contributing to structural changes in local governance and increasing cross-sectoral cooperation. The opportunities of children and young people to participate in matters relevant to them has been expanded. One of the key aspects of the initiative in Finland is that citizens and stakeholders have become more informed of the rights of the child. The whole municipality is committed to the application of the model.

One of the previous shortfalls in Finland regarding the rights of the child was the limited consideration of children and young people from vulnerable and minority backgrounds in the development of programmes relating to children and young people in general. Any existing shortcomings or barriers to the progress of Child Friendly Municipalities are raised at the evaluation meetings facilitated by local UNICEF staff every two years.

Best practice: information, training, and enabling participation

So how can children and young people be included and considered more in local decision making? The approaches municipalities across Finland have adopted as part of the initiative involve informing, training and listening in the form of consultations and providing opportunities for children and young people to influence service design.

The emphasis is on holistic and long-term transformation, which means tailoring approaches to different groups of children and young people based on their wants and needs.

Examples from Finland show that the creation of coordination groups that bring together different departments in local government has been essential in facilitating change. The flow of information has been improved by streamlining strategic documents to include specific sections relating to children and young people [https://unicef.studio.crasman.fi/pub/public/pdf/hyvat-kaytannot-lapsiystavallinen-kunta.pdf]. Stakeholders across sectors have also been involved in informal consultations where their experiences and ideas of what works best have been collated to inform further activities.

Consultations have also included children and young people through interviews or online surveys to make sure any new approaches are reflecting the wants and needs of different aged children.

A look at approaches for including children and young people in the design of services and initiatives shows the recognition of different age groups.

The city of Hämeenlinna – where the Child Friendly City initiative was first piloted – has taken into use a participation guide, dividing under 30-year-olds into 6 age groups based on participation strategies from playground design and school activities to communication strategies. The city also utilises an online discussion platform where children and young people can share ideas and vote for ideas they support. Other approaches to participation include creating a local children’s parliament specifically for primary school aged children.

Younger children’s participation has been expanded through activities in nurseries such as weekly meetings to discuss past and future activities, as well as activities where values and experiences are explored through play and drawing.

The holistic premise of the initiative means that extracurricular activities are as important as activities relating to educational settings. One municipality offers free hobby passes for secondary school-aged children to encourage teenagers to continue their extracurricular activities such as swimming.

Other examples include providing a youth centre for digital and conventional gaming for 16+ year-olds and employment workshops for under 30-year-olds interested in the creative media sector. Children and young people’s use of public space has been explored, for example, through workshops where school-aged and young people share their experiences of urban space to an audience of local politicians and youth council members. Less conventional and creative approaches such as participatory applications based on video recordings and interactive mapping have also been used to understand children and young people’s experiences of public space to highlight the need for improvement.

Not all smooth sailing

Feedback from municipalities participating in the initiative highlights some challenges. An evaluation completed by a Finnish consultancy identified that municipalities find the language used in the model impractical and the rights-based terminology challenging to comprehend.

Stakeholders felt that the aspects relating to the participation of children and young people demand most of their attention, despite being only one of several buildings blocks of the model. The following are some of the main highlighted barriers for the initiative in Finland:

- a general lack of resources

- lack of structures to report the engagement of children and young people

- lack of data to inform the improvement of existing practice.

Overall, the initiative suggests that more needs to be done to take children and young people into account when it comes to urban settings. This goes beyond providing a safe environment with educational and extracurricular opportunities. The emphasis is on making sure these surroundings are designed based on the views of different groups of children and young people. While there is a lot of emphasis on inclusion and participation, the groundwork has to be done by city governments to make urban governance, decision making and implementation more inclusive.

The Child Friendly City initiative is a continuous process facilitated by regular evaluation. It is worth noting that not all Finnish municipalities have continued with the initiative as resources are tight and introducing the model across a whole municipal organization can be demanding.

As Cardiff embarks on the journey to become a Child Friendly City, it should look in all directions to make sure approaches are age-specific and needs-based.

Strategies aiming to increase the involvement and visibility of children and young people should be based on addressing existing caveats, something that a variety of research streams at WISERD and Cardiff University can contribute to.