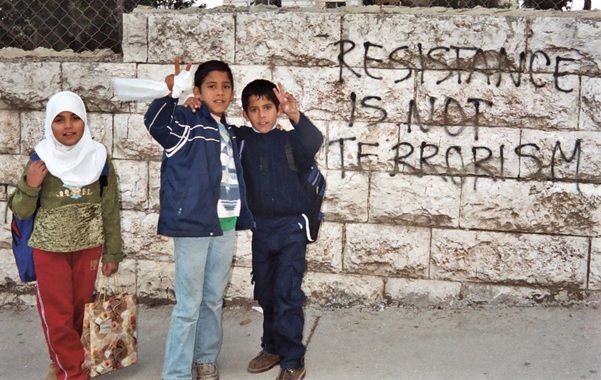

New research by WISERD Co-director Professor Paul Chaney examines civil society perspectives on children’s rights in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. The study confirms widespread violations of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Since 1967 Israel has occupied the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. In 1980, Israel officially annexed East Jerusalem and has claimed the whole of Jerusalem as its capital. This is a troubled context, for although in 1990 the State of Israel ratified the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), it disputes that its obligations extend to the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT).

Despite UN condemnation, in consequence, there has been a dearth of official data and scholarly attention to the situation. The new analysis from WISERD uses critical discourse analysis to examine civil society organisations’ reports submitted to the 2018 third-cycle United Nations’ Universal Periodic Review (UPR), the five-yearly official monitoring mechanism associated with UN rights treaties.

Key Findings

The analysis underlines how children face widespread rights violations – including education and healthcare, maladministration in criminal justice, sexual abuse and poverty. Space constraints preclude a full discussion here. Instead, violence and education will be used as examples.

Article 19 of the CRC requires that, ‘States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse’. However, violence is the first-ranked violation in the civil society UPR discourse. Repeated accounts refer to violent attacks by Israeli settlers on children. For example, ‘Expansion of settlements and settler violence… [we] collected testimonies from women on the prominence of arbitrary settlers’ violence, especially against women and children. They reported that many women fear their children will be injured, arrested, or killed for being in the wrong place at the wrong time’.

A key issue is violence towards children from the Israeli authorities. For example, there were 590 West Bank children detained and prosecuted under the jurisdiction of Israeli military courts between 2012 and 2016. The data show that 72 percent of children endured some form of physical violence following arrest and 66 percent faced verbal abuse, humiliation, and/or intimidation.

CRC Article 28 asserts that ‘States Parties recognize the right of the child to education…’ Yet Article 28 violations were the second-ranked issue in the Third Cycle UPR discourse. For example, one CSO noted that: ‘recurrent conflict and occupation has negatively impacted education with widespread arrest and detention of children and youth; and restrictions on movement including access to schooling’.

War damage and its consequences for education is a further key trope. Over 200 schools in the OPT have been destroyed by Israeli attacks. CSOs highlighted how this constituted collective punishment of civilians in the region. Others reported how violations were not restricted compulsory phase education. They alluded to attacks on ‘university campuses and students, especially arrests of student activists, discriminatory policies, the violation of the freedom of movement including the movement of academics.’

Significance?

In contrast to civil society views, analysis of the Israeli Government’s UPR discourse shows how it seeks to give the external impression to the international community that it is engaging with UN monitoring processes. Yet the endurance of children’s rights violations in the OPT means that in the case of Israel, the UPR process is characterised by performativity and legitimation – effectively, in colloquial terms “going through the motions”. As Israel’s denial of responsibility for the OPT attests, it lacks any intent to fully comply with the Convention of the Rights of the Child in the Occupied Territories.

The urgent need for critical evaluation of state practices is further underlined by the recent raft of Israeli legislation constraining civil society. This suggests that civil society organisations should not boycott the UPR. In an increasingly repressive political context for NGOs, their use of the UPR to criticise the Israeli Government’s children’s rights record in the OPT is of vital importance. Ahead of the fourth cycle UPR in 2023, future progress will depend on securing greater international awareness and state responsiveness to civil society views. Without this, children will continue to suffer widespread human rights violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

You can read the full research findings in the forthcoming Open Access international journal article:

Chaney, P. (2021 forthcoming) Civil Society Perspectives on Children’s Rights in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, The International Journal of Children’s Rights, ISSN: 1571-8182