Dr Stuart Fox suggests there was no real increase in youth turnout at last year’s election

After the polls closed in the 2017 general election, the ‘youthquake’ quickly became one of the hottest talking points amongst academics, politicians and journalists alike. Driven on by photographs on social media of young people queuing outside polling stations, evidence of strong Labour results in constituencies with large numbers of students mobilised by the party’s promise to scrap university tuition fees, footage of rallies in which Jeremy Corbyn was cheered to the rafters by thousands of young supporters, and opinion polls making (highly questionable) claims of high youth turnout, many quickly concluded that we were witnessing a ‘youthquake’ that had deprived the Conservatives of their majority in the House of Commons and propelled Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour to a spectacular result.

Claims such as the ‘youthquake’ are, however, hard to verify, because official statistics do not provide any demographic information about who turns up at polling stations. We are inevitably forced, therefore, to rely on imperfect estimates of the turnout of particular groups (such as young people) from sources such as surveys or constituency level estimates. The face to face British Election Study (BES) is the ‘gold standard’ survey when it comes to studying electoral behaviour in Britain. While it still suffers from many of the short-comings associated with surveys and opinion polls (such as the difficulty in recruiting politically disengaged participants), it does have the key advantages of first spending far more time and resources recruiting a more representative sample than most opinion polls are able to, and of being able to provide validated data on electoral participation, i.e. it matches respondents to the electoral register and so can accurately report whether or not they voted.

Today, the BES team released their data for the 2017 general election, and with it an analysis of the differences in turnout between 2015 and 2017. Contrary to the story of the ‘youthquake’, they showed that there was no significant difference between the turnout of young voters (18-24 year olds) in 2017 and that in 2015. While there is little question that the majority of young people who did vote supported Labour (and so at least that aspect of the ‘youthquake’ claim is supported), there was no disproportionate increase in the youth vote to herald an end to the debates about why young people are less likely to vote than previous generations at the same age.

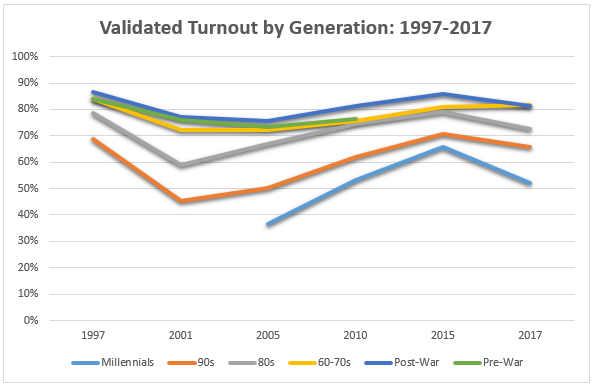

If we compare the 2017 BES data with that from previous BES surveys, we can see how this fits within the trend of the Millennials’ political participation, i.e. the generation of young voters who first started to enter the electorate after the 1997 election and for whom events such as 9/11, the Iraq War, the financial crisis, the expenses scandal, the ‘age of austerity’ and now Brexit have been defining features in their political socialisation, and who in 2017 were aged between 18 and 35. The graph below shows that most recent data marks the continuation of a trend that has characterised the Millennials since they first appeared: they remain consistently less likely to vote than older generations, even when those generations were the same age. While more Millennials voted in 2015 and 2017 than ever before, their turnout continues to lag behind that of their elders.

Source: British Election Study

Another prominent feature of the ‘youthquake’ theory is that young people had become more engaged with politics, and that the 2017 campaign proved that if politicians engage with young people effectively they will vote in high numbers. This reflects the oft-cited (but rarely tested) conventional wisdom that today’s young people are politically alienated, put off by the repeated failures of the political elite to make them feel that politics was worth engaging with. Following the 2017 result, many suggested that this was changing, as Millennials were enthused by Jeremy Corbyn’s political values and passionate opposition to austerity, and as a result of the experience of being on the ‘losing’ side of the EU Referendum and remaining implacably opposed to Brexit.

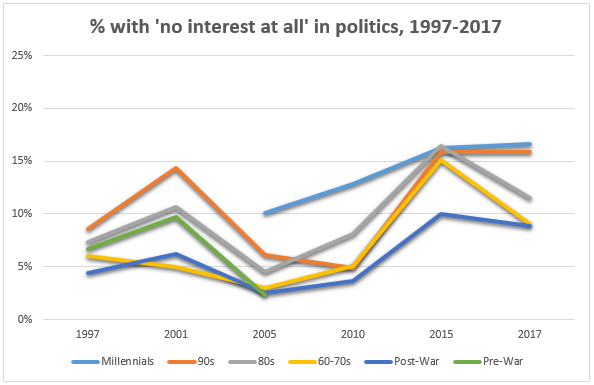

The BES data also undermines this theory, however. The chart below shows the proportion of respondents in each generation who reported having no interest at all in politics in every election since 1997. Consistent with previous research that has identified the Millennials as the least politically engaged generation in the electorate, and this trait as the key factor behind their comparatively low electoral turnout, the data shows the Millennials as the most likely generation not to have any interest in politics. While only a minority of respondents of any generation report being completely uninterested, the Millennials are less likely to have high interest in politics as well: 14% reported being ‘very interested’ in politics in 2017, compared with 20% of the 90s generation, 19% of the 80s generation (or ‘Thatcher’s children’) and 26% of the 60-70s generation (or ‘baby boomers’).

Source: British Election Study

The data also shows that there was no notable shift in political interest between 2015 and 2017 either. In 2015, three quarters of Millennials were ‘fairly’ or ‘not very’ interested in politics; 9% were ‘very interested’ and 16% had no interest at all. This compares with 70% who were ‘fairly’ or ‘not very’ interested in 2017, 14% who were very interested, and 17% who were not at all interested. While there was a tiny increase in the proportion of Millennials who were ‘very interested’ in politics, the difference is not statistically significant, and there was no corresponding fall in the proportion who had no interest at all.

Despite the repeated claims of the ‘youthquake’, therefore, the best survey data we have shows that there has been no significant increase in electoral turnout or political engagement amongst young people between the general elections of 2015 and 2017. In a sense, this may seem surprising – if young people’s interest in politics isn’t going to be increased by a nation-wide referendum about an issue they care passionately about, or the election of party leader who places more emphasis on youth politics than any of his predecessors and appears to have an unmatched appeal amongst them, what will actually affect it?

This is entirely consistent, however, with what we know about political interest and electoral turnout: they are habitual. People who get into the habit of voting, or of being interested in and engaging with politics, while young are more likely to continue to do so throughout their adult lives. Conversely, those who get into habits of non-voting and political apathy are likely to remain disengaged. It takes dramatic events, such as wars or financial collapses, to ‘over-write’ the habits we develop during youth. The lesson we can take from the myth of the ‘youthquake’ is that it will take a lot more hard work to reverse the decline of political interest and electoral participation amongst younger generations than a referendum and/or a change in party leadership.