WISERD Education has been exploring children’s responses to a single question: ‘If someone gave you £1 million today, what would you do with it?’ Although such an exploration might seem trivial, we argue that their responses provide important insights into children’s values and priorities.

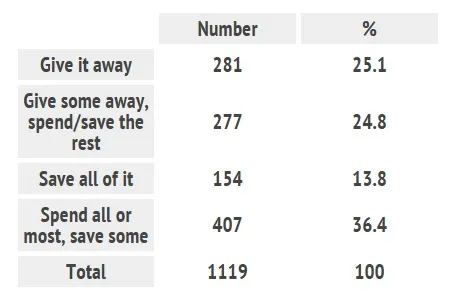

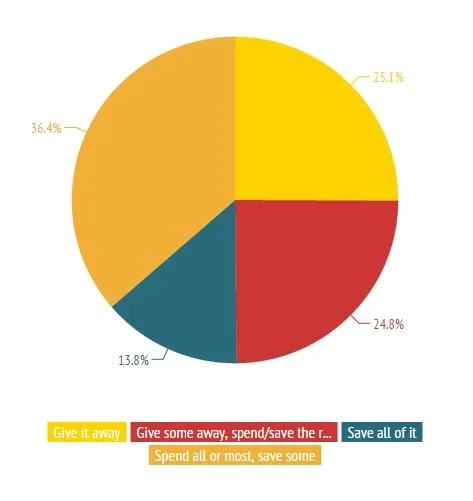

The data from which this paper draws derive from a self-completion survey undertaken in 2013 by three cohorts of school children (aged 10, 12 and 14) in the HEFCW-funded WISERDEducation research programme. They attended 29 schools primary and secondary schools serving very different kinds of communities (advantaged/disadvantaged, rural/urban, Welsh-speaking/English-speaking) across Wales. The distribution of responses can be seen in the table below:

We were really surprised at the large proportion who said they would give it away. Nearly one in ten would give it to charities – with Cancer Research being the most frequently mentions. More than one in ten would give it to family and friends – often to alleviate financial hardship and pay off debts.There were some very touching responses:

“I would move my taid’s grave to my nain’s grave so my dad will be happy that his mum and dad are together”

“Help my mum have a lung transplant”

“Spend it all on my Granddad who’s got cancer”

Even those who were planning to save or invest the money often had altruistic intentions.

“I would invest so I could keep giving to people who need it. I would also make sure I have enough to be comfortable, but I wouldn’t be greedy”

The responses of those who were going to spend all or most of the money were perhaps the most predictable – revealing highly gendered spending ambitions (e.g. boys wanting fast cars) and a desire for celebrity status (e.g. spending the money on ‘boy bands’).

While these young people’s responses are only fantasies and we have no way of knowing what they would actually do if someone gave them £1 million, we want to argue that their intentions are worthy of our attention on a number of grounds.

Money itself is the ultimate representation of social interdependence – and therefore what children want to do with it will embody the kind of social relations they would like to see fostered. The dominant theme of giving and sharing that runs through many of their responses is an expression of the preferred relationships between themselves, their family friends and the wider society.

Relatedly, if we believe their intentions are statements of social preferences, it would appear that the discourse and values of neoliberalism are less hegemonic than is often suggested. The large proportion intending to give all or some of the money away suggests that these young people have not been socialised into celebrating individualism at the expense of broader collective obligations.

Finally, also noteworthy are the marked differences in response within this group of children. While altruistic intentions were surprisingly common, they were by no means universal and we should not ignore the large proportion of children who did intend to spend the £1 million on themselves. The fact that we have strongly contrasting intentions indicates that there are divergent social processes and circumstances which merit further investigation. What is it that leads some children to be predominantly ‘givers’, some to be ‘savers’ and others to be ‘spenders’?

About the author: Professor Sally Power is the Director of WISERD Education, and Co-Director of WISERD. She is based at Cardiff University. Her research interests focus on the relationship between education and inequality, and particularly social class differentiation, as well as the relative success and failure of education policies designed to promote greater equality of opportunity.