There is no denying that the disruption to daily life caused by the coronavirus pandemic had a profound influence on children’s well-being, with various international organisations (eg, WHO, UNESCO, WFP, UNICEF) requesting that more be done to assist children in coping with this, to avoid long-term negative consequences.

In Wales, data from the 2021 International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISCWeB) – Children’s Worlds, an international research survey on children’s subjective well-being – has found that overall levels of subjective well-being amongst children, specifically in urban areas, appear to have worsened since 2018.

What data did we use?

Prior to the pandemic, UK reports already indicated declining levels of children’s well-being and this has only accelerated during the last few years, as ¼ million children reported not coping well with changes during the pandemic.

To understand and evaluate the influence of the pandemic on well-being, measurements of well-being prior to the pandemic must be included, where available. Consequently, data from the Children’s Worlds surveys provides an opportunity to study changes in the overall subjective level of well-being in Wales for two age groups (10-year-olds in primary schools and 12-year-olds in secondary schools) before and during the pandemic.

Data from the pre-pandemic wave in 2018 can be compared with data collected during the pandemic, as they used the same metrics to assess changes over time. Although not all schools that participated in the first wave also participated in the second wave and vice versa, the indicators used in this analysis were included in both questionnaires.

What did we do?

Using data from the 2018 and 2021 waves of the Children’s Worlds survey, the level of subjective well-being was assessed by asking children about overall satisfaction with their life, and several specific aspects of their lives too (eg, use of their time, their freedom, their health) before and during the pandemic, in primary and secondary schools, and in both urban and rural areas.

What did we find?

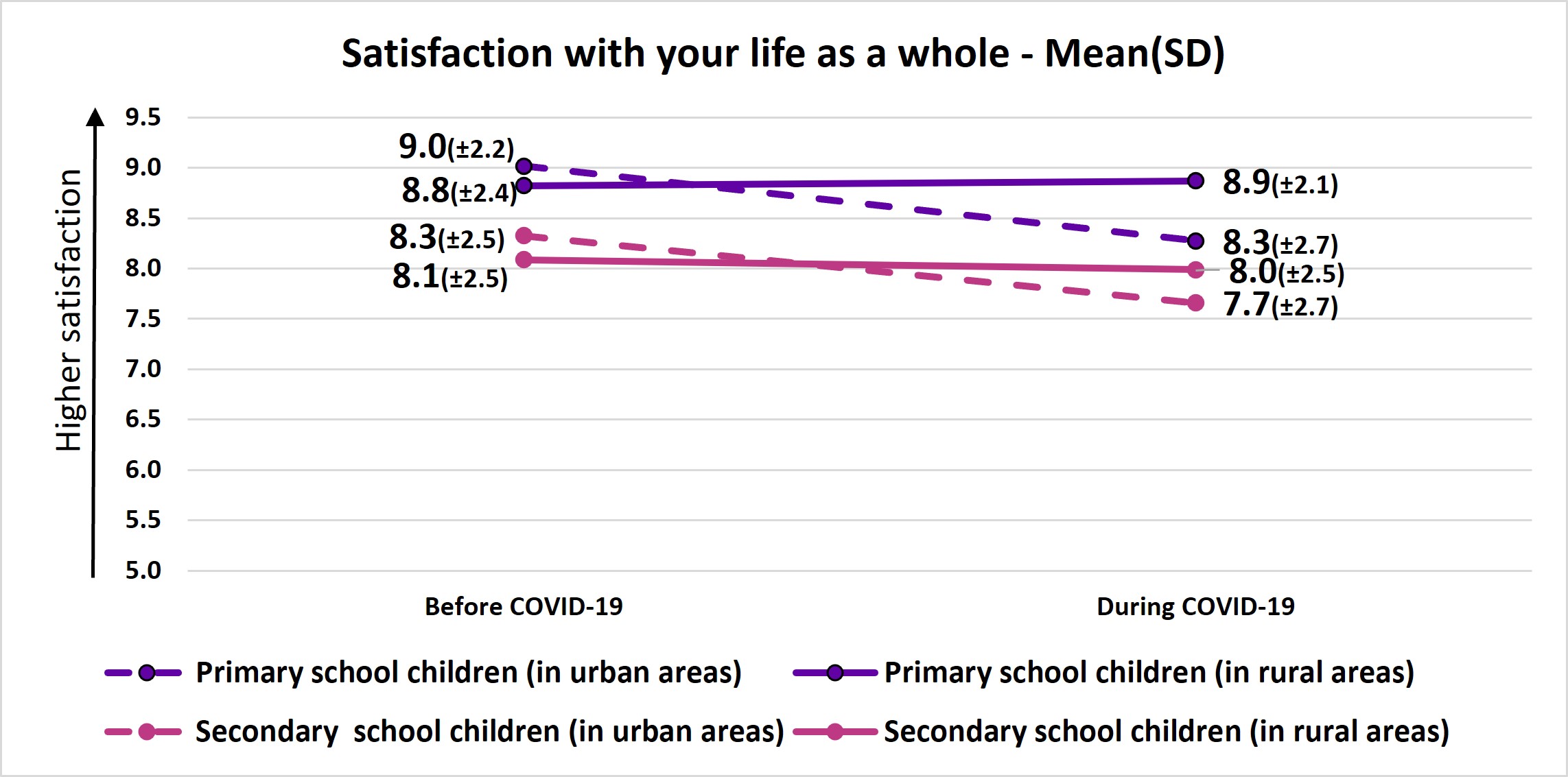

Since 2018, there has been a decrease in overall life satisfaction amongst both age groups (10- and 12-year-olds) for children in schools in urban areas. Furthermore, for the older age group, regardless of whether they attended urban or rural schools, levels of self-reported well-being worsened during the coronavirus pandemic (Figure 1).

Importantly, we did not observe a significant decline in levels of well-being amongst all children. For example, there was actually a very small increase in levels of life satisfaction amongst primary school aged children in rural areas, and for secondary school children in rural areas, levels of life satisfaction only declined slightly.

This suggests that the impact of the pandemic on children’s well-being was most notable in urban areas of Wales. This could be due to a greater impact of lockdown restrictions or more tangible impacts of the pandemic in urban areas, or greater levels of resilience in rural areas.

Figure 1 – Pupils’ satisfaction with their life as a whole – mean (SD): before and during the coronavirus pandemic

Figure 1 – Pupils’ satisfaction with their life as a whole – mean (SD): before and during the coronavirus pandemic

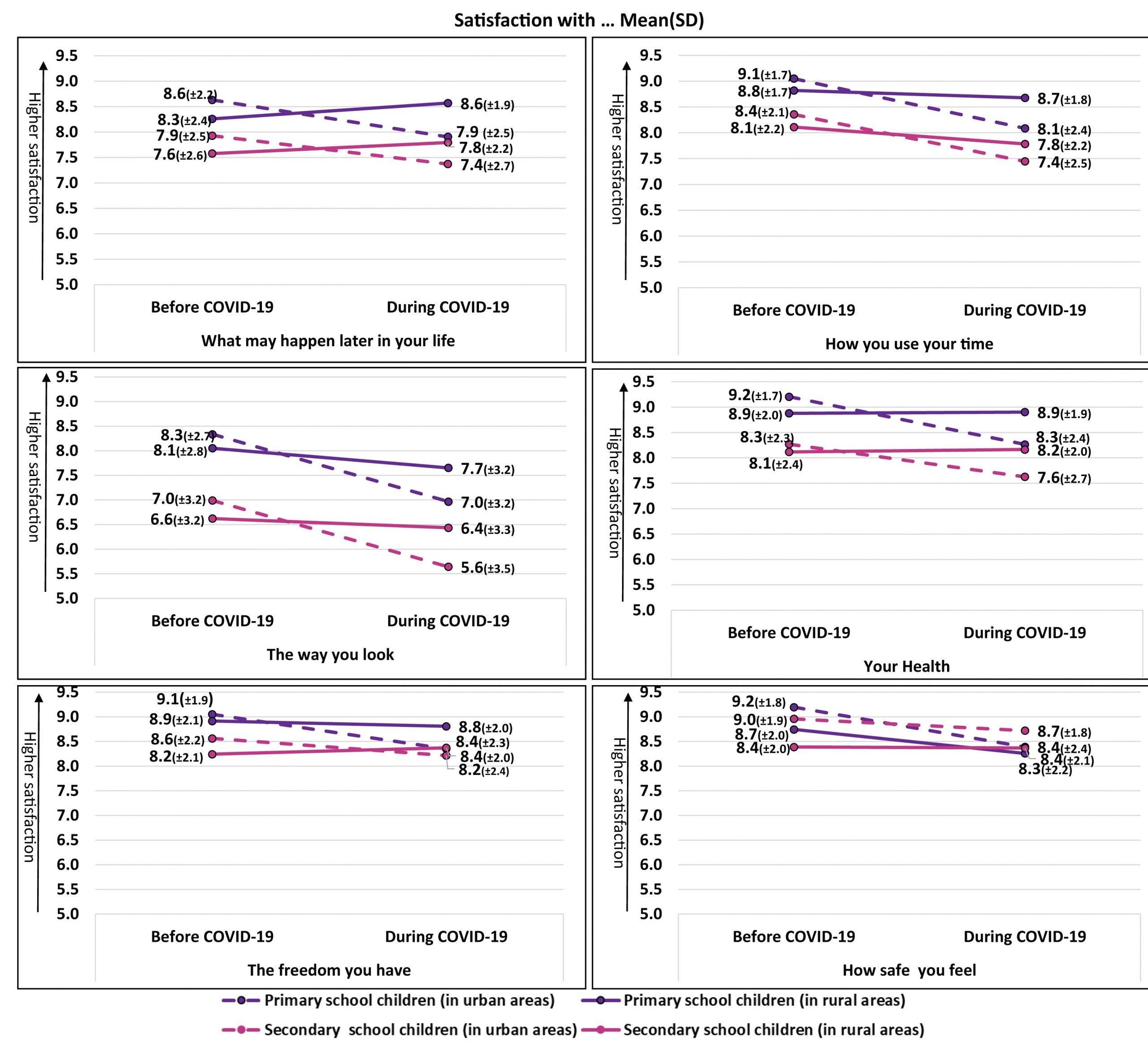

Similar patterns were observed for children’s happiness with various aspects of their lives – when tested for statistical significance (t-test), the differences were significant for pupils in urban areas. Children from urban areas, regardless of age, generally showed a decrease in their self-reported satisfaction in specific areas of their lives. Overall, the measure of well-being that deteriorated the most was in relation to their appearance, which was generally lower for children in urban areas than rural areas before the pandemic (Figure 2), and how children spend their time.

As with overall life satisfaction, other measures of subjective well-being for children in rural areas improved between 2018 and 2021. Indeed, satisfaction with health and with what might happen later in life improved for secondary school children in rural areas.

Some caveats to these results should be noted. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional study, therefore it does not track the same pupils across time, but rather two separate cohorts. Even though the survey was distributed to the same schools in the first wave, only a few schools participated in both waves. Finally, due to constraints of the pandemic (eg, varying levels of access to the internet), the sample in the second wave is smaller than the first (691 pupils from 20 schools compared with 2,600 pupils from 54 schools).

Figure 2– Pupils’ satisfaction with various aspects of their life – mean (SD): before and during the coronavirus pandemic

Figure 2– Pupils’ satisfaction with various aspects of their life – mean (SD): before and during the coronavirus pandemic

What next?

The next blog post in this series will focus on pupils’ satisfaction with further specific aspects of their life (eg, family, school, friends) before and during the coronavirus pandemic. Moreover, as data for all countries that took part in the survey is now available, the next phase of the research will be to see how changes in Welsh children’s subjective well-being during the pandemic compares to that of children in other European countries.

Disclaimer

The data used in this publication comes from Children’s Worlds: An international survey of children’s lives and well-being (www.isciweb.org). The views expressed here are those of the author. They are not necessarily those of ISCWeB.

Image credit: bodnarchuk via iStock.