A global demographic shift means that an ageing population creates an unprecedent demand for adult social care. We live in an era when, for the first time, the number of older people (60+ years) will exceed younger people1. In the UK this challenge is magnified by the effects of austerity and welfare state capacity.

New research by WISERD Co-Director, Professor Paul Chaney, studies the political response to what the UK Prime Minister has called a “crisis in social care”2. Attention centres on political parties’ competition to attract voters’ support as they seek a mandate for their diverse manifesto pledges on care delivery in Westminster, Scottish and Welsh and Northern Irish elections (1998-2019). This research is significant because, although adult social care is a politically-charged issue, the electoral politics of it has previously been overlooked in academic work.

Adult social care in the UK

Adult social care refers to non-medical support to adults in need, typically arising from old age. In the UK, the number of 85+ years individuals with complex care needs is expected to increase in the next two decades. In England alone, recent estimates suggest that there are 940,000 people with dementia. This is predicted to increase 57% by 2040. According to the latest UK parliamentary report: ‘The case for making a sustained investment in social care has never been stronger… We urge the Government to now address this crisis as a matter of urgency… An immediate fuding increase is needed to avoid the risk of market collapse caused by providers’3.

In response to the increasing demand for adult social care across the nations of the UK, political parties have increased their attention to it over successive elections:

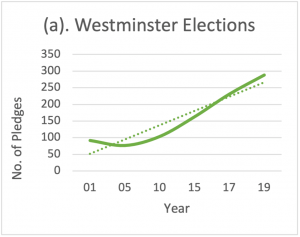

- In Westminster manifestos, the number of pledges triples (+307 percentage points. Figure 1a) making it one of the most pressing policy challenges of the past two decades.

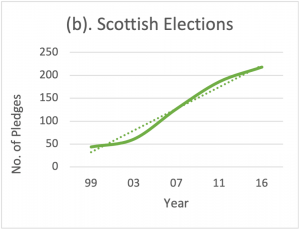

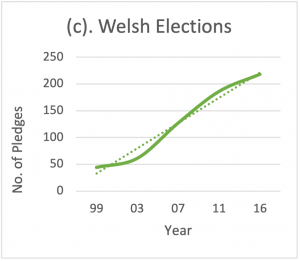

- In Wales and Scotland, the growth is consistent across election cycles (aside from a minor decrease in 2003) (Figures 1b and c).

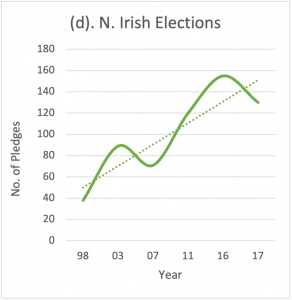

- In Northern Ireland, electoral attention is more variable (Figure 1d). This is due to the fragility of devolution in the province rather than indicating less need for it.

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Level of attention (“Issue Salience”) to Adult Social Care in UK Elections 1998-2019 (No. of Pledges).

The study also shows how manifesto pledges territorialise adult social care policy in the different nations of the UK. In other words, electoral politics lead to distinctive and contrasting social care policy in the different territories. For example:

- On wages and employment terms (e.g. ‘Labour will lead the way on sectoral bargaining in areas where government spending can influence, for example in the care sector’, Scottish Labour 2016, p.27) and, new legal protections (e.g. ‘Violence against health and social care workers is unacceptable and a growing concern. We will consult on the options to increase the protection for these important workers’, Scottish Liberal Democrats 2007, p.12).

- Civic nationalist parties’ manifesto pledges on adult social care are likely to be framed in opposition to central government (i.e. Westminster) policies. In Scotland, the SNP’s discourse is linked to party demands for independence. For example, ‘The current Westminster benefits arrangements cannot lift many carers out of poverty. With Independence, we would have the power to tackle this shortcoming through our comprehensive review of tax and benefits’ (SNP 2003, 15).

- In Wales, Plaid Cymru’s resistance to Westminster policies is evident from the outset of devolution. For example, ‘We see an important opportunity for the National Assembly to challenge the right-wing views that currently dominate London politics… Plaid Cymru believes that market mechanisms, introduced by the Conservatives and continued by New Labour under the guise of Best Value, have been inappropriate and damaging’ (Plaid Cymru 1999, 6).

Conclusion

The impact of devolution on social welfare in the UK is leading to geographically distinctive and contrasting approaches to adult social care across the four nations. This study tells us about the importance of language in electoral politics and how parties seek to persuade voters to back their policies. It underlines the inherently political nature of policy issues like adult social care.

In England, policies have a greater emphasis on market-based solutions which contrast with the mixed economy of welfare approaches of the dominant Left-of-Centre/ civic nationalist parties in Wales and Scotland.

References:

[1] United Nations (2015) World Population Ageing: Report, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, NY: UN. P.3

[2] UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, BBC Interview 14 January, 2020 https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/boris-johnson-social-care-plan-bbc-breakfast-election-latest-a9282611.html [Last Accessed 03.03.21]

[3] House of Commons Select Committee on Health (2020) Report on Social care: funding and workforce, London: House of Commons, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmhealth/206/20602.htm [Last Accessed 03.03.21]

To read the research findings in full:

Chaney, P. (2021 forthcoming) Exploring the Politicisation and Territorialisation of Adult Social Care in the UK: Electoral Discourse Analysis of State-wide and Meso Elections 1998-2019, Global Social Policy, SAGE Publishing, ISSN: 1468-0181 (print); 1741-2803 (web).

Chaney, P. (2021 forthcoming) Exploring the Politicisation and Territorialisation of Adult Social Care in the UK: Electoral Discourse Analysis of State-wide and Meso Elections 1998-2019, Global Social Policy, SAGE Publishing, ISSN: 1468-0181 (print); 1741-2803 (web).

© CC-BY licence – Open Access

This research was undertaken as part of: Trust, human rights and civil society within mixed economies of welfare | WISERD in WISERD’s ESRC Civil Society Research Programme led by Professor Ian Rees Jones.