The 1984-85 miners’ strike has once again hit the headlines, despite ending 36 years ago. This time what has grabbed the media’s attention is a claim by Prime Minister Boris Johnson that Margaret Thatcher’s closure of the pits after the strike was part of a green, eco-strategy of the Conservative government.

On a visit to Scotland, Johnson was asked about the government’s preparations for the global environmental conference, COP26 to be held in Glasgow in November. He said that in his lifetime the UK had transitioned away from coal and that this was a process begun by Margaret Thatcher:

He is reported as then laughing and saying to reporters: “I thought that would get you going.”

His comments caused a major political row with widespread condemnation of both the tone and a rejection of the content of what he said. For example, Welsh First Minister, Mark Drakeford told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme:

“I’m afraid that those remarks are both crass and offensive.

Johnson refused to apologise, although Tory MPs representing so-called ‘red wall’ constituencies were reportedly worried about the impact of his ‘massively damaging’ remarks.

The truth is that there is no evidence that environmental concerns played any part in Thatcher’s determination to run down the coal industry in the 1980s. By contrast there is a great deal of evidence that her real motives were to deal a mortal blow to the industrial power of the National Union of Mineworkers as part of a broader attack on the trade union movement.

Before the 1979 general election, the Tories commissioned the Stepping Stones report from Thatcher’s adviser John Hoskyns and Norman Strauss from Lever Brothers and an action plan drawn up by Nicholas Ridley (both in 1977). The Stepping Stones report identified ‘the negative role of the trades unions’ as one of the major obstacles to ‘national recovery’. The ‘Ridley Report’ was leaked to the Economist in May 1978 setting out detailed plans for the next Tory government on how to approach the nationalised industries. A special annex on ‘Countering the political threat’ was essentially a strategic manual for confronting and defeating the unions, chief among them being the miners.

We carried out research into the motivations behind today’s trade union membership and activism in South Wales (with Helen Blakely, Rhys Davies and Huw Beynon). The 1984-85 strike plays a big part in the collective memory, even among those who were too young to have taken any part in it. Our data fits with the observation of Beynon and Hudson that there exists within the coalfield communities an intergenerational ‘tribal memory’ and that:

…through kin, proximity and a remembered past, coal mining had played a significant role in the national culture. (Beynon H and Hudson R (2021) The Shadow of the Mine, London: Verso, pp. 4, 151)

The participants in our research had no doubts about the reasons for the pit closure programme – and it had nothing to do with a green energy strategy. One union activist from the Ebbw Fach Valley who worked in local government in 1984 saw the actions of the state as straightforwardly ‘an attack on trade unionism’.

The Thatcher government’s motives were described in some detail by another trade unionist at the other, western edge of the coalfield. He took on the environmental argument and accepted that coal mining was making a loss but felt that:

“if it had been phased out gradually and replaced with other industries … people would have accepted that coal is … a fossil fuel. We need to look after the Earth. Not BANG! Because … there was an ulterior motive that was just to destroy the unions and … Wales paid a particularly heavy price.”

Yet another union activist, from the head of the Sirhowy Valley in the east of the coal field remembered how his brother had been a miner and reflected: “Well I think they were closing pits for their own political ends really.”

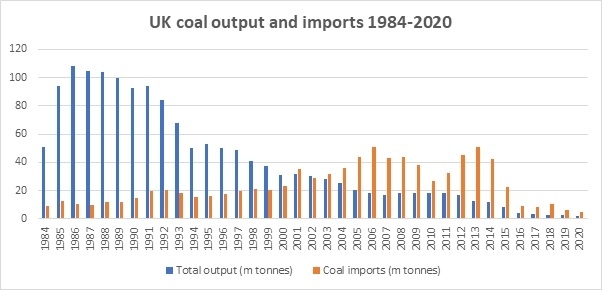

Lest there be any doubt that the Conservatives had few objections to coal as a fuel so long as it didn’t come with a strong union attached, we only have to look at the UK output of coal from the mid-1980s onwards together with the figures for imports of coal. Within an economy that had an overall declining use of coal in its energy mix, it is notable that although domestic production steeply fell, imports of coal rose and remained significant right up until 2014-15.

Source: DBEIS (2021) Historical coal data: coal production, availability and consumption 1853 to 2020 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/historical-coal-data-coal-production-availability-and-consumption Accessed 9 August 2021

Mrs Thatcher’s programme of pit closures was not motivated by any far-sighted recognition of the dangers of fossil fuel to the environment. The objective was to weaken the trade unions – that she described as the ‘enemy within’ – and which she regarded as a barrier to ‘national recovery’. Her view was that the economic crises of the 1970s could only be overcome and profits revived by reducing the ability of unions to prevent pay cuts and defend the public sector.

The real legacy of the pit closure programme in Wales is not so much the greener valleys (an accidental by product) but the decades long combination of unemployment, under-employment, ill health, increased crime and drug use and lack of hope. Many parts of the valleys have still to recover from this.

As one union activist from the west of the coalfield reflected:

“Thatcher killed, killed this town… we were always tainted with that brush of, of what Thatcher did to us to be quite honest.”

Image credit: Big Pit: National Coal Museum. Wales. By Loco Steve via Flickr. Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)