UK unemployment has risen to its highest in two years this month, from 3.9% in March to 4.1% in September. Young people aged 16-24 have been hit hardest and, to date, one-third of 18-24 year olds (excluding students) are unemployed or furloughed as a result of COVID-19, compared to one in six of 25-40 year olds. To add to this unease, 35% 18-24 year olds are now earning less than they did before March 2020, compared to 23% of 25-49 year olds. Currently youth unemployment in the UK stands at 12.7%. This blog explores the response from civil society organisations in the UK nations to this crisis.

Umbrella organisations across the UK– such as Youth Employment UK, YouthLink Scotland, Young Scot, the Council for Wales of Voluntary Youth Services, the Ethnic Youth Support Team for Wales and Youth Action Northern Ireland, to give just a few examples – are currently leading on youth-centred policy responses, engagement sessions and offering employability resources for young people. Other organisations continue to firefight on the ground by providing practical support such as laptops for young people, assistance with benefit claims, housing and mental health. In a previous blog about my research on youth unemployment I showed some variation in size and geographical classification between these civil society organisations working in youth unemployment in the four nations of the UK. In this blog I will set out my latest analysis of the way in which these organisations describe their work in the context of COVID-19. Read a more in-depth report on my recent research.

To frame my findings I have drawn on a study by Hobbins, Eriksson, and Bacia (2014) looking at civil society strategies under different welfare regimes across Western Europe. As I mentioned in the previous blog, no other study has applied these frameworks to the UK’s unique devolved arrangements. Addressing this knowledge-gap is the purpose of my ESRC funded research project.

Using Hobbins, Eriksson, and Bacia’s study and a methodology developed by Chaney and Wincott (2013), I have analysed UK civil society organisation’s objectives as set out in their entries in two key databases – the Charity Commission database and 360 Degree Funding data. Deductive coding of these entries allowed me to identify the following organisational distinctions in their approaches to youth unemployment:

Civil Society Organisation Approach |

Description |

|---|---|

| (1a) Structural view of youth unemployment | Youth unemployment as one part of a bigger problem (e.g. poverty), government takes responsibility. |

| (1b) Individualised view of youth unemployment | Youth unemployment as an individual problem, individual takes responsibility. |

| (2a) Policy-orientated | A focus on advocacy, lobbying, co-working with government. |

| (2b) Service-orientated | A focus on delivering services like training and mentoring. |

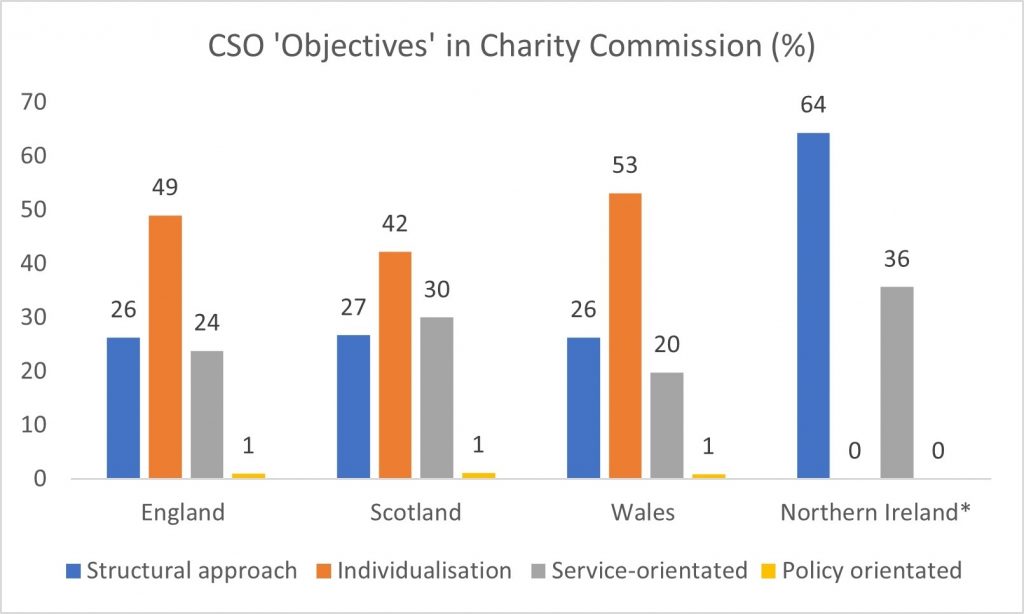

Looking at the Charity Commission data in Table 1 (below), Northern Ireland has by far the highest proportion of civil society organisations emphasising a structural view of youth unemployment with 64% of analysed objectives indicating a structural, or more holistic approach. This approach would view the youth unemployment as part of a wider social problem, like poverty or inequality, and the charity’s objectives would include words like ‘citizenship’, ‘empowerment’, ‘poverty’, ‘equality’, ‘justice’ ‘deprivation’ and ‘diversity’.

Table 1: Civil society organisation objectives in Charity Commission database (%)

Number of CSOs =E:2968, S:3248, W: 128, NI: 3460

Charity objectives emphasising an individualised view of youth unemployment (in other words, the problem is the individual being out of work) are highest for Wales (53%), then England (49%) and then Scotland (42%). Charity objectives here include the use of words like ‘employment’, ‘employability’, ‘skills’, ‘training’, ‘career’ and ‘internships’. The lack of individual emphasis from civil society organisations in Northern Ireland compared to the other three countries is something that needs further investigation through more in-depth content analysis and fieldwork interviews, planned for autumn 2020.

Strikingly, policy-orientated approaches with civil society organisations are very poorly represented in all four countries. However, organisational size may explain this. A large politically orientated civil society organisation advocating on behalf of other organisations as well as young people, such as Youth Employment UK, would only be counted once in this analysis despite its reach and influence going far beyond and encompassing many smaller civil society organisations. This is a key issue to explore further through my fieldwork.

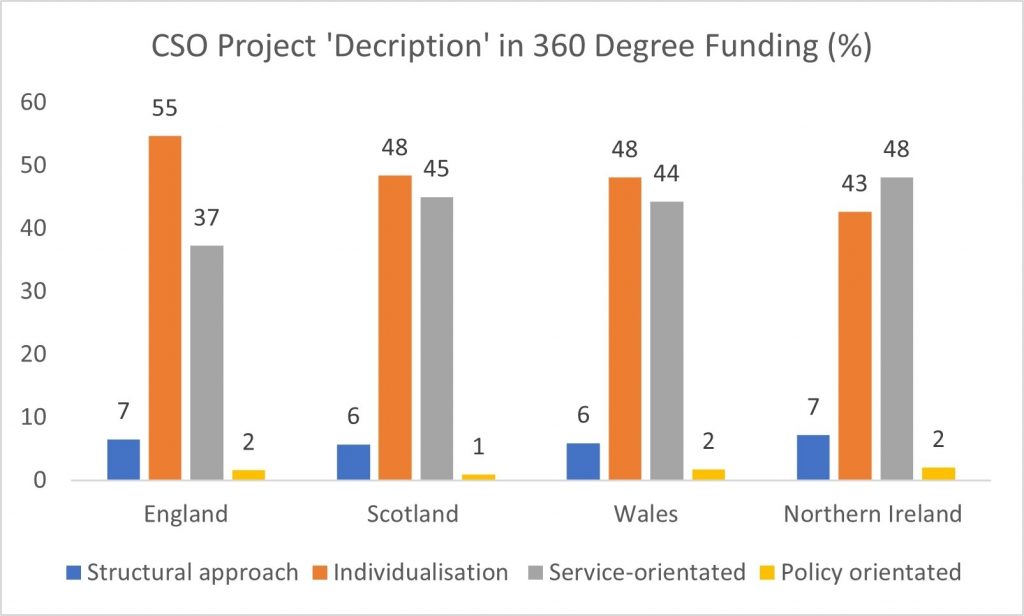

Table 2: Civil society organisation project description in 360 Degree Funding (%)

Findings from the 360 Degree Funding data are presented in Table 2 (above) and show a much lower level of signifiers emphasising a structural view of youth unemployment and a much higher emphasis on an individual view of youth unemployment in all four countries.

Of note, and in-line with the different policy approaches, civil society organisations in England put the strongest emphasis on the individual and employability, followed by Scotland and Wales then Northern Ireland. This is a key finding and is significant because it underlines the centrality of political-economy analysis to understanding the divergent civil society approaches to tackling youth unemployment in sub-state welfare regimes in the UK.

Three reflections on this. Firstly, despite small variations, patterns around youth unemployment are similar in all four countries and broadly reflect a liberal welfare regime: individualised approaches to employment focusing on skills and training and a service-orientated approach. This could lead us to conclude that devolution has not had a significant impact on civil society working in the field of youth unemployment; despite the more social democratic policy rhetoric in the devolved territories. However, previous research such as that by Hazenberg et al, carried out in in 2014, shows social enterprises working within different ecosystems in England and Scotland which contradicts what is shown here. Secondly, the method used here allows us to gain a UK-wide understanding of the shape, size and broad approach of thousands of civil society organisations and to compare them, but it does not go beyond the charity’s own description of its aims. For this reason, the findings presented here are only one piece of the puzzle. Finally, the data does show small differences in policy approaches by civil society organisations, with England putting the strongest emphasis on the individual and employability, followed by Scotland and Wales then Northern Ireland. This key finding makes further investigation into divergent civil society approaches to tackling youth unemployment in sub-state welfare regimes – like the UK – a valuable learning opportunity.

With youth unemployment set to rise at the end of the government furlough scheme in October, along with in-work poverty, precarity, job-insecurity and flexible working causing mental health issues, housing problems and long-term scarring effects amongst young people; based on the data presented here, a more holistic approach to addressing youth unemployment is worth considering. An approach going beyond employability and towards confidence-building and empowerment and tackling the structural causes of unemployment and precarity would, arguably, offer a more appropriate response to the current youth unemployment crisis than those framed in terms of narrowly defined macro-economic interventions by the state and transfer payments via social security.

Find out more about the project: ‘Youth unemployment and civil society under devolution: a comparative analysis of sub-state welfare regimes’