Mae'r cynnwys hwn ar gael yn Saesneg yn unig.

The idea that Brexit has engaged the young to such an extent that they voted in high numbers in the recent general election has been a prominent feature of the public autopsy of the result.[1] There is little question that the young voted in greater numbers than in the last half dozen elections, and that this had a substantial (though not decisive) impact on Labour’s performance in particular. In light of the persistent reluctance of many Millennials to vote in the past, this is a welcome change. But has Brexit affected their broader engagement with politics at the same time as their propensity to vote?

The political engagement of Millennials is distinctive in many ways, one of which is a lower level of political interest. While they maintain an active interest in specific political issues, they tend to be less interested in the processes, institutions and actors associated with British democracy than their parents and grandparents were at the same age. This generational difference is illustrated in Figure One, which uses data from both the British Election Study and WISERD’s Young People & Brexit survey[2]. Only a minority of the British electorate can be described as entirely apathetic, but the Millennials stand out for entering the electorate with higher levels of apathy than their predecessors. This is a cohort effect – whereby the youngest generations are growing up developing habits of lower interest in politics than their elders, and even despite changes that occur throughout the life cycle (such as people becoming more interested in politics once they get established careers, purchase houses, have children, etc.) they are likely to remain less interested throughout their adult lives.

Source: British Election Study; YouGov

Brexit, however, and the political climate created by EU Referendum and the 2017 election, could challenge this. First, if we look at the 2017 data point in Figure One, it is clear that while political apathy has fallen somewhat for every generation, it has fallen most of all for the Millennials: in 2015, one in five Millennials had no interest at all in politics, but by the 2017 election, this had fallen to fewer than one in ten.[3] Second, our survey also asked what (if any) political activity our respondents had engaged in throughout the past year to influence Brexit (regardless of whether they supported or opposed it). We already know that many young people voted with the intention of influencing Brexit, but using data from the Audit of Political Engagement we can also compare how many were taking part in protests, signing petitions or joining or donating to political parties or campaign organisations in response to Brexit with how many reported doing so in the winter of 2015 (ie, after the 2015 election but before the EU Referendum).

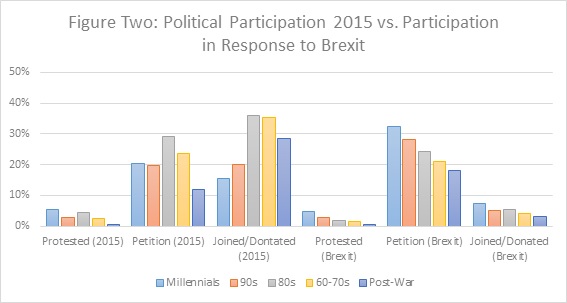

The results are presented in Figure Two. In 2015, around 5% of Millennials protested, 20% had signed a petition, and 16% joined or donated to a political group. A smaller proportion reported joining or donating to political groups because of Brexit (just 7% – though this fall is apparent across all generations), the proportion protesting was the same, while the proportion signing a petition increased to 32%. There is some evidence of the young becoming more politically active as a direct consequence of Brexit, specifically being more likely to vote and to sign petitions (though this doesn’t extend to all forms of political activity).

What is more notable about Figure Two, however, is the way that the Millennials’ participation compares with that of older generations. In the 2015 data, the Millennials were slightly more likely to have protested, more likely than the Post-War but less likely than the 80s and 60-70s generations to have signed a petition, and less likely than all generations to have joined or donated to a political group. In response to Brexit, however, the Millennials are more likely than their elders to have protested, signed a petition and joined or donated to a political campaign. The only act they are not more likely to have done is voted.

Source: Audit of Political Engagement; YouGov

This trend is indicative of a myth often attributed to the young: that they are less likely to vote but more likely to engage in ‘alternative’ political activities and avoid party politics and politicians. However, once the fact that everyone in the electorate has become more likely to participate in ‘alternative’ acts such as protesting or signing petitions over the last forty years is taken into account, the young are no more likely to do such things than anyone else. This makes the fact that the Millennials are clearly more active in response to Brexit even more remarkable: they are not necessarily becoming more politically active than their elders in our Brexit-dominated political climate, but they are more likely to be active outside the electoral arena because of Brexit. This suggests, therefore, that Brexit is indeed having a politicising effect on Britain’s young. The Millennials are the most politically apathetic generation ever to have entered the British electorate – and yet in direct response to Brexit they are becoming more politically engaged and active, reducing the difference between themselves and their elders. It is far too early to know whether or not this trend will continue, but the fact that there is the potential for the Millennials to become newly politicised and engaged after Brexit is encouraging nonetheless.

[1] The exception, oddly, appears to be supporters of the Labour Party, who despite plenty of evidence to the contrary reject the view that Brexit had anything to do with the youth vote, and insist it was a response to Jeremy Corbyn’s political agenda and personal appeal.

[2] The survey was conducted online by YouGov Plc. on a representative sample of the adult British population. The sample size was 5,095, with fieldwork conducted by 9th-13th June. The weighted data is representative of the adult British population. More information can be obtained from the authors on request.

[3] Note that the data for 2017 is based on the proportion of respondents who said they had no interest at all in Brexit and the general election, rather than no interest in politics.