Mae'r cynnwys hwn ar gael yn Saesneg yn unig.

If you keep track of key measures of disability equality in the UK, you’ll know that the gap in employment rates between disabled and non-disabled working-age people has gone down over the past fifteen years. And you’d be in good company. Many experts have flagged this trend: Dame Carol Black in her influential 2008 Review, DWP indicators 2009-2015 and a recent editorial in the British Medical Journal (BMJ). It is on the basis of this trend that the OECD considers the UK to be more successful than its neighbours in integrating disabled people into the workplace.

But if you thought this, you might be wrong.

At the same time as one group of researchers claimed that the disability employment gap was going down, another group – including two papers in the BMJ (here and here) and a report by leading expert Richard Berthoud – were writing about how the disability employment gap was going up. Partly this is explained by a difference in time period (starting from 1998 compared to the late 1970s) but, even focusing on the same period (1998-2012), this latter group find no change in the disability employment gap. The difference in trends arises from choice of survey. Those who find that disabled people are catching up in terms of their employment rate have used the Labour Force Survey (LFS), while those who find no change have used the General Household Survey (GHS). Importantly both surveys are collected and published by Government, are based on a random sample of households and measure disability in the same way, namely as a longstanding illness or disability that limits daily activities.

Without explanation or reconciliation (or even a dialogue between the two groups), the most basic question in disability research, ‘has the disability employment gap gone down?’, cannot be answered. In a recent journal paper three social scientists Ben Baumberg, Melanie Jones and Victoria Wass turn their attention to this long-standing anomaly, the resolution of which is crucially important for policy-makers.

There are lots of differences between surveys which could give rise to differences in disability employment gaps, though not perhaps differences in trends in those gaps. These include differences in the methods used to interview people (e.g. telephone or face-to-face) and differences in areas of the country included. Looking into all of these details and restricting the analysis to only those parts of the surveys that are strictly comparable, harmonised employment gaps are compared across the different surveys. Results from a third high-quality survey that no-one has previously used in this context, the Health Survey for England (‘HSE’), is also included.

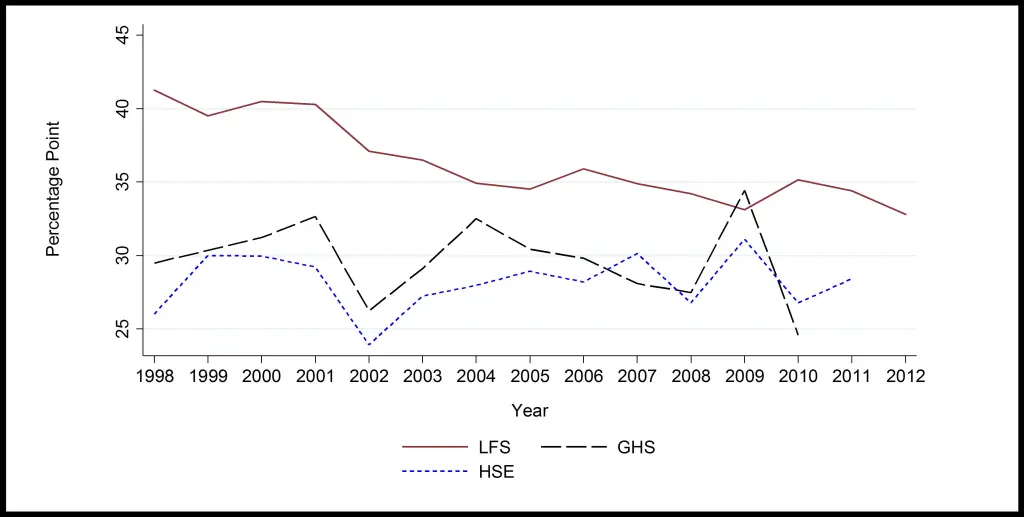

Trends for all three surveys are published in Social Science and Medicine (open-access) and show that the same puzzling differences in trends remain after harmonisation: the LFS shows an improving trend towards greater equality in employment. This trend is not evident in the HSE or GHS. You can see this in the figure below.

Disability employment gaps in harmonised samples across surveys (1998-2012)

One potentially important difference in the LFS is that the proportion of working-age people reporting disability has been rising steadily and there is a strong association between the level of disability reporting and the disability employment rate in the LFS. This makes sense – the people who move across the borderline between reporting and not reporting a disability are likely to be less severely disabled than people who will definitely report a disability. In contrast, in the HSE and GHS, disability reporting has been relatively stable – if anything it’s been falling over time – and it is not strongly linked to the employment rate. Until we understand why disability has increased in the LFS (but not in other surveys), we cannot conclude that employment prospects for disabled people have improved.

The LFS measure is the main policy-evaluation tool used by Government. Since the trend in the LFS is inconsistent with trends in other surveys, it should not be relied upon as the sole indicator of the disability employment gap in the UK.

Suggested further reading:

Berthoud, R. (2011). Trends in the employment rates of disabled people in Britain. ISER Working Paper Series 2011-3, University of Essex.

Berthoud, R., & Blekesaune, M. (2006). Persistent employment disadvantage, 1974-2003. ISER Working Paper Series 2006-9, University of Essex.

About the authors:

Ben Baumberg is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology and Social Policy at the School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research (SSPSSR) at the University of Kent, and Co-Director of the University of Kent’s Q-Step centre.

Melanie Jones is a Professor of Management Economics at Sheffield University. She is an associate of the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods (WISERD), and a member of the Wellbeing Connect research network. She is also an associate editor of Economic Issues.

Dr Victoria Wass is a Reader at the Cardiff Business School. She teaches Evidence-based Management on the MBA and Executive MBA programmes. Her research interests span labour economics, sociology of work and HRM and include studies of disability at work and the organisation of work in the Police service.