Mae’r naratif ynghylch addysg wyddoniaeth yn y DU ac yn fyd-eang yn aml yn cael ei fframio o amgylch “piblinell sy’n gollwng”. Er bod yn ofynnol i bob disgybl astudio gwyddoniaeth tan 16 oed, mae llawer yn camu i ffwrdd ohoni ar ôl yr adeg hon. Mae sawl ffactor dros ddatgysylltu: gwahaniaethau rhwng y rhywiau, rhwystrau economaidd-gymdeithasol, poblogrwydd pwnc (mathemateg a bioleg yn trechu ffiseg) ac, erbyn hyn, mae tystiolaeth sy’n dod i’r amlwg yn awgrymu y gallai ffactor arall chwarae rôl – sgiliau iaith.

Mae ein hymchwil ddiweddar yn archwilio agwedd newydd ar ddilyniant gwyddoniaeth, technoleg, peirianneg a mathemateg (STEM): sut mae cyflawniad mewn astudiaethau Saesneg neu Gymraeg yn dylanwadu ar benderfyniadau disgyblion i barhau â gwyddoniaeth y tu hwnt i TGAU.

Cipolwg ar yr astudiaeth

Fe wnaethom archwilio carfan o bron 9,000 o ddisgyblion a oedd yn dilyn cwrs UG mewn ysgol a gynhelir gan y wladwriaeth (chweched dosbarth) yng Nghymru yn 2017/18. Fe wnaethom grwpio’r disgyblion hyn ar sail eu graddau TGAU mewn gwyddoniaeth, mathemateg a Saesneg/Cymraeg:

- Cyflawnwyr Uchel: Gradd A neu uwch mewn mathemateg, gwyddoniaeth, a Saesneg/Cymraeg.

- Cyflawnwyr Gwyddoniaeth: Gradd A neu uwch mewn mathemateg a gwyddoniaeth, gradd B neu is mewn Saesneg/Cymraeg.

- Cyflawnwyr Iaith: Gradd A neu uwch mewn Saesneg/Cymraeg, gradd B neu is mewn gwyddoniaeth a mathemateg.

- Cyflawnwyr is: Gradd B neu is mewn mathemateg, gwyddoniaeth, a Saesneg/Cymraeg.

Cyfeiriwyd at y disgyblion yn y ddau grŵp cyntaf fel Myfyrwyr Gwyddoniaeth Posibl – y rhai sydd mewn sefyllfa dda i lwyddo mewn gwyddoniaeth ôl-16. Labelwyd y ddau grŵp olaf fel myfyrwyr gwyddoniaeth annhebygol – disgyblion y mae llai o ddisgwyl iddynt barhau â gwyddoniaeth mewn addysg ôl-16.

Pwy sy’n dewis a phwy sy’n aros mewn gwyddoniaeth?

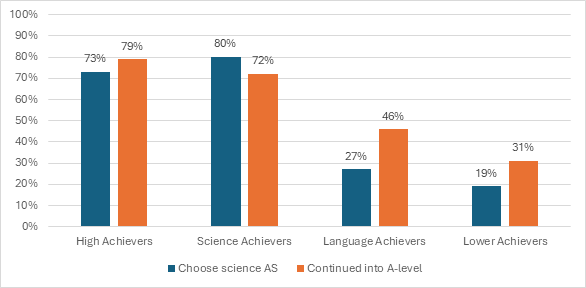

Datgelodd y canfyddiadau rhaniad diddorol:

- Dewis ar Lefel UG: Dewisodd tua 80% o Gyflawnwyr Gwyddoniaeth bwnc gwyddoniaeth, o gymharu â 73% o Gyflawnwyr Uchel. Ond mae’n nodedig y dewisodd tua chwarter o Gyflawnwyr Iaith ac Is i astudio gwyddoniaeth, er eu bod yn cael eu hystyried yn “annhebygol.”

- Parhad i Safon Uwch: Roedd Cyflawnwyr Uchel yn arwain y ffordd, gyda 79% yn parhau â gwyddoniaeth i Safon Uwch. Roedd Cyflawnwyr Gwyddoniaeth yn dilyn, sef 72%, tra bod llai na hanner y Cyflawnwyr Iaith a Chyflawnwyr Is yn parhau.

Gallai’r patrymau hyn, a ddangosir yn Ffigur 1 (isod), awgrymu bod hyfedredd iaith yn bwysig. Mae disgyblion cryf ar draws y tri phwnc (gan gynnwys iaith) yn fwy tebygol o barhau â gwyddoniaeth, hyd yn oed os yw eraill yn ei ddewis i ddechrau.

Ffigur 1

Gwahaniaethau ar lefel pwnc

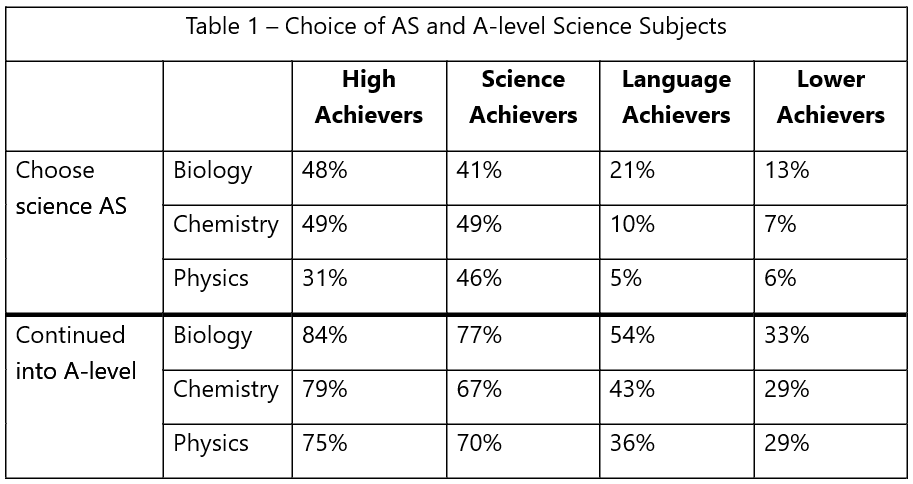

Mae’r data hefyd yn ailddatgan stereoteipiau pwnc fel y dangosir yn Nhabl 1 (isod):

- Ffiseg: Poblogaidd ymhlith Cyflawnwyr Gwyddoniaeth ond yn amlwg yn cael ei hosgoi gan eraill.

- Bioleg: y wyddoniaeth fwyaf poblogaidd ar gyfer Cyflawnwyr Iaith ac Is, ac yn gystadleuol ymhlith y Cyflawnwyr Uchel a Gwyddoniaeth.

- Cemeg: Y wyddoniaeth fwyaf poblogaidd ymhlith Cyflawnwyr Uchel a Gwyddoniaeth.

Tabl 1

Pam mae hyn yn bwysig

Os ydym yn mesur y nifer sy’n astudio gwyddoniaeth Safon Uwch yn unig, rydym mewn perygl o anwybyddu cam hanfodol: yr “hidlo” UG. Mae llawer o ddisgyblion yn gadael gwyddoniaeth ar ôl Blwyddyn 12, cam sy’n siapio llwybrau prifysgol a gyrfa.

- Myfyrwyr Posibl Coll: Nid oedd tua un o bob pump o Gyflawnwyr Gwyddoniaeth yn astudio gwyddoniaeth ar ôl TGAU, er gwaethaf graddau cryf.

- Myfyrwyr Annhebygol wedi’u Hennill Roedd miloedd o Gyflawnwyr Iaith neu Is yn dangos diddordeb mewn gwyddoniaeth, gan herio disgwyliadau.

Gyda chymorth wedi’i dargedu, gallai ysgolion helpu’r ddau grŵp i ffynnu. Er bod gan Gyflawnwyr Is y gyfran isaf o ddisgyblion sy’n dewis gwyddoniaeth ar lefel UG, nhw yw’r grŵp mwyaf, gan gyfateb i oddeutu 1,000 o ddisgyblion. Dychmygwch pe bai gan y 1,000+ o ddisgyblion hynny a ddewisodd wyddoniaeth y sgiliau i lwyddo – gallent newid tirwedd STEM y dyfodol.

Symud ymlaen

Mae’r mewnwelediadau hyn, a gyflwynwyd yn ddiweddar yng Nghynhadledd ADR UK 2025 yng Nghaerdydd, yn tynnu sylw at bwysigrwydd ehangu ein persbectif. Nid yw gallu gwyddoniaeth yn ymwneud â mathemateg ac arbrofion yn unig – mae sgiliau iaith yn sail i ‘lythrennedd gwyddoniaeth’ disgyblion – eu gallu i ddehongli, gwerthuso a chyfathrebu cysyniadau gwyddonol.

Bydd ymchwil yn y dyfodol yn archwilio cyfraddau llwyddo ar draws y grwpiau hyn, gyda’r bwriad o nodi’n union ble gall ymyriadau helpu myfyrwyr i aros mewn gwyddoniaeth a llwyddo. Bydd hefyd yn archwilio dewisiadau’r ‘Myfyrwyr Posibl Coll’ – pa bynciau y mae gwyddoniaeth yn cystadlu â nhw? Oherwydd mewn byd sy’n gofyn fwyfwy am lythrennedd gwyddonol, dylai pob disgybl sy’n dangos diddordeb mewn gwyddoniaeth gael ei annog a’i gefnogi’n ddigonol i’w ddilyn.