Mae'r cynnwys hwn ar gael yn Saesneg yn unig.

WISERD’s Professor Melanie Jones blogs for The Conversation with Professor Victoria Wass, Cardiff University.

Disability affects the lives of millions of people in the UK. With about one in six working-age people currently reporting some kind of disability, around 70% are either working, looking for work or want to work. Good quality work is important for both their health and well-being and contribution to the wider economy. Yet, despite high rates of employment across the population as a whole, only half of disabled people are in work.

Campaigners have long called for a greater focus on the job opportunities for disabled people: for more support in the recruitment process and to raise job retention rates for people who become disabled in work. This challenge has been increasingly recognised by the government, including in the recently launched strategy on employment for disabled people, Improving Lives.

The government has made formal commitments to increasing the employment rate for disabled people. Understanding and assessing progress towards disability employment targets requires regular production and monitoring of national statistics. This becomes difficult when the commitments change. It becomes impossible when the data series stops being published.

All change

When the government launched its new strategy, there was an important change in how it measured progress. The Conservative party manifesto in 2015 promised to halve the disability employment gap – that’s the difference between the employment rate of non-disabled people and the same for disabled people – by 2020. In its 2017 manifesto, and in the Improving Lives strategy, this was changed to committing to see a million more disabled people in employment by 2027.

The government suggests that its new commitment is better than its previous one. It said: “Both commitments are ambitious and far-reaching, but the new one is specific and time-bound.”

In fact, both are time-bound and specific but, in the context of an increasing number of disabled people in the working-age population, and rising employment rates within the economy, the second is a much weaker commitment. This was recognised by the shadow minister for disabled people, Marsha De Cordova. At the strategy launch, she expressed regret that the first commitment has been replaced with the second less ambitious target.

Mind the gap

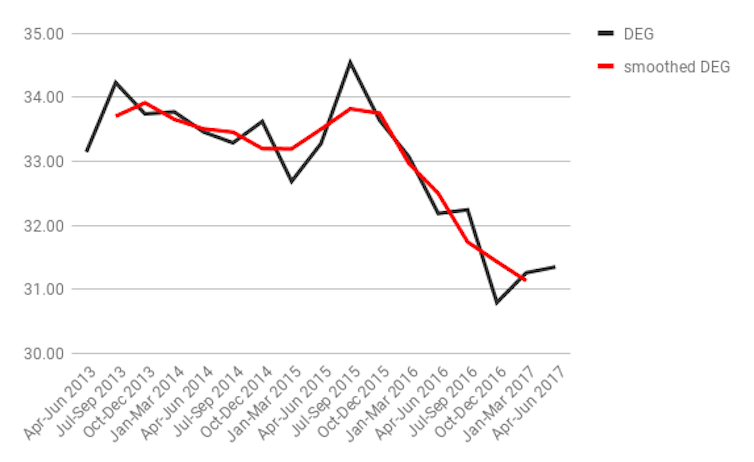

The disability employment gap, measured as the percentage point difference between the employment rates of non-disabled and disabled people of working-age, was 33.1 percentage points in April 2013 and 34.5 percentage points at the time it was made the subject of the Conservative government’s commitment (July 2015).

As the graph below shows, progress has been positive but small. The gap had narrowed by 1.8 percentage points between April 2013 and June 2017. But meeting the 2015 manifesto commitment requires a narrowing of 16 percentage points. At this rate of progress, fulfilling its commitment would take 37 years (until 2054) – beyond the working lifetime of anyone currently aged over 30.

Disability employment gap (percentage points) 2013-17

So, the government may meet its new target. But this implies nothing about meeting its original commitment to narrow the disability employment gap. Relative to non-disabled people, disabled people could continue to be disadvantaged to the same extent that they are now and the government can claim success in meeting its new commitment.

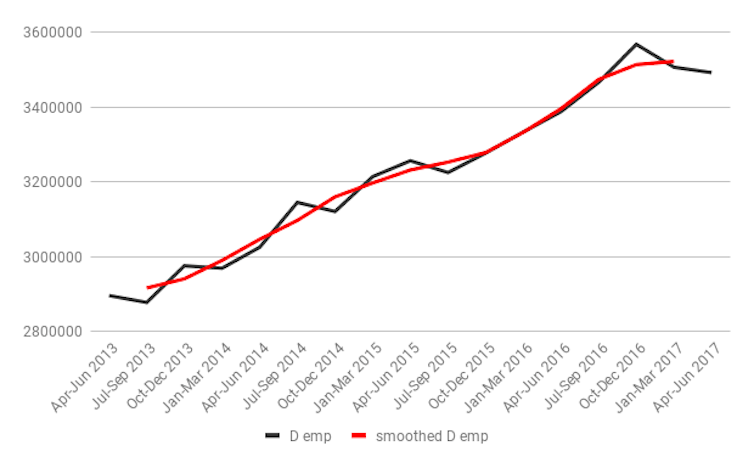

Disability disadvantage is a relative concept and absolute numbers can be misleading as a guide to progress on equality and inclusion. The expansion in jobs for disabled people (596,000) looks less impressive when set against an increase in the population of working-age disabled people of 458,000 and an increase in the number of non-disabled people in employment of 1,455,000.

The government should be judged on both its commitments.

The missing quarters

The sharp-eyed reader will also notice a reversal of progress on both commitments in the first two quarters of 2017. The disability employment gap has widened and the number of disabled people in employment has fallen. Short-term survey data which track minority groups are volatile and can be misleading in identifying trends. Longer term “smoothed” trends (shown in red) are more reliable.

Statistics for the second two quarters of 2017 will help distinguish whether this recent widening gap reflects short-term volatility or a reversal of the narrowing trend. With unfortunate timing, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) is unable to release this information.

It’s been 6 months since any data was collected on the disability employment gap. We can’t make policy or hold the gov to account without that information. Urging the @ONS to reinstate that dataset as a matter of urgency. pic.twitter.com/wI2yGVYhDf

— Marsha de Cordova MP (@MarshadeCordova) February 22, 2018

We have been told this is due to a problem with data quality but we have been given no further details and there is no sign of when it might be resolved. When the series restarts, it will be important that the statistics are comparable otherwise the analysis of trends and the scrutiny of progress will be impossible.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Photo credit: Rawpixel.com on Shutterstock