Mae'r cynnwys hwn ar gael yn Saesneg yn unig.

Rhys Davies explores how he uncovered problems with official UK government figures on trade union presence and coverage – and how the government recognised and corrected the error.

In a time when trade union membership is decreasing in both the UK and the USA,

The decline in union membership has been well documented for many economies across the globe in recent decades. The long-term downward trend in union membership in the UK is well known. Based upon membership returns submitted annually by individual trade unions to the Certification Office, trade union membership within the UK peaked in 1979 at approximately 13.2 million. Since then, there has been a precipitous decline. Estimates published by the UK Government based upon the Labour Force Survey places the current number of union members within Great Britain at approximately 6.7 million (DBEIS 2018).

This decline in union density is related with the shift in the industrial and occupational composition of employment away from traditional `heavy industries’ over the last four decades, the restructuring of the state (including privatisation, and contracting out and cutting public services) and the emergence of the `new economy’ characterised by the associated forms of precarious employment. It’s heartening for those who see the advantages of trade union membership and collective bargaining on pay and conditions to read a recent Financial Times report “The upstart unions taking on the gig economy and outsourcing” which highlighted the growth of new, smaller unions often self-arranged by workers in lower-paid and/or more precarious employment.

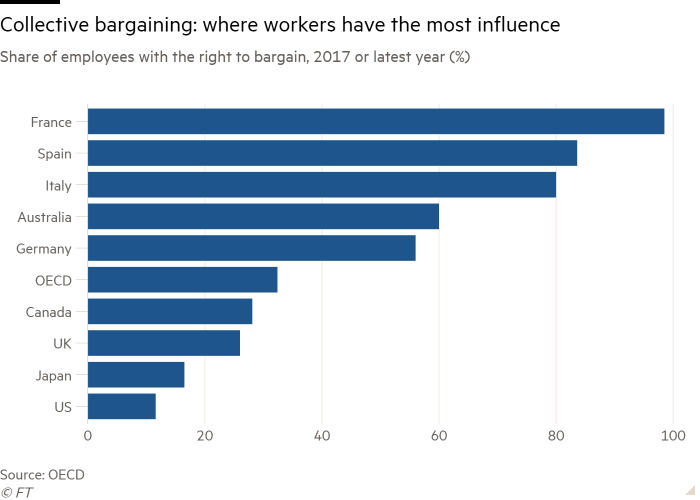

Included in the article was a graphic depicting the relative influence of trade unions in a range of countries, based upon data collated by the OECD from national sources. The analysis suggests that UK workers exhibit relatively low levels of coverage by collective bargaining arrangements compared to other OECD members. Those employed in the gig economy will undoubtedly fair much worse.

Image: Collecting bargaining: where workers have most influence, based on OECD figures.

My recent research however has uncovered that official statistics for derived by the UK government do not in fact give an accurate representation of the trade union presence and coverage for the UK. As a result, the true picture of trade union coverage for the UK is not as bleak as that portrayed in the Financial Times.

But how could the official statistics have got this wrong?

My research explored the use of the UK Labour Force Survey (LFS) in producing statistics on union membership and discovered a number of contributory factors to under-reporting.

The research looked at three areas which survey data could give information about:

- Union density: The percentage of those in employment who are a trade union member.

- Union presence: Whether or not a trade union or staff association is present within a workplace.

- Union coverage: Whether the pay and conditions of employees are agreed in negotiations between the employer and a trade union.

Assessing union coverage

Our research compared estimates of union coverage derived from the Labour Force Survey with those derived from other sources of data, including the Skills and Employment Survey, the Workplace Employment Relations Survey, Understanding Society and the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings. The analysis revealed that the official measures of trade union coverage based upon the LFS were 40% lower than those based on other sources. The problem stems from a difference in the wording of the question used in the LFS compared to the other surveys. Whilst the LFS asks whether the pay and conditions of the respondents are ‘directly affected’ by agreements between employers and trade unions, other surveys simply ask whether unions and staff associations are ‘recognised’ by management for the purposes of negotiation. The wording of the LFS question therefore not only asks respondents to consider the involvement of trade unions and staff associations in negotiations over pay and conditions, but it also implicitly asks respondents for an assessment of there effectiveness.

Assessing union presence

Within the LFS, union presence is established by asking respondents if they are a member of a union or, if not, whether they are employed at a workplace where others are. If the answer to either of those questions is yes, that respondent is regarded as being employed at a workplace where trade unions are present. Analysis revealed that around 15% of LFS respondents fail to provide the responses necessary to derive union presence. This is perhaps not surprising. For example, approximately a third of responses to the LFS are provided by proxy; typically the partners of the target respondent. Union membership is clearly an area where proxy respondents may be unaware of their partner’s membership status or of the presence and coverage of trade unions within their partner’s workplace. The target respondents themselves may also not be aware of the membership status of their colleagues.

Generally, in statistical analysis, respondents with missing data such as this would not be included in the derivation of rates of union presence as either their membership status or that of their colleagues cannot be assumed. However, analysis revealed that official estimates of union presence retained these respondents within the analytical samples, treating these groups as if they had reported that there was no union present in their workplace. This skewed the results of official statistics downwards.

Supporting a better understanding of trade union membership

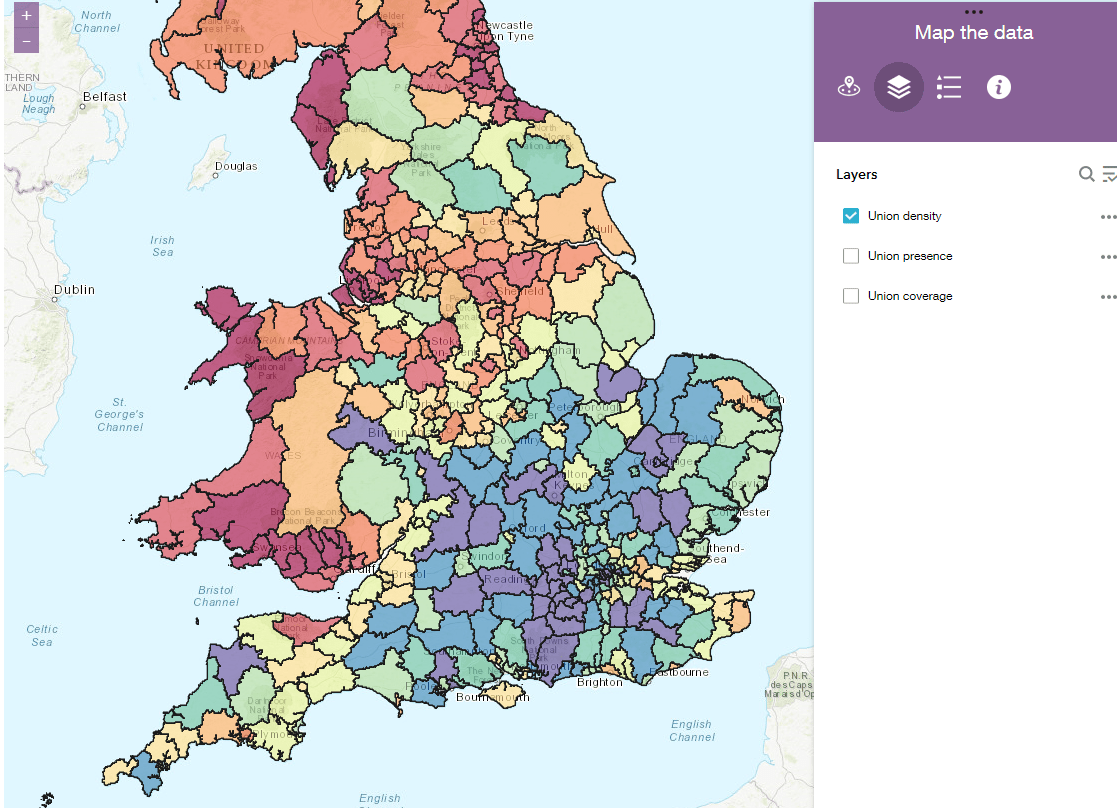

In undertaking this research we also produced

• a statistical compendia which provides the most comprehensive statistical portrait of regional variations in trade union membership, presence and coverage in the UK undertaken to date

• the UnionMaps website which presents estimates of trade union membership for across Unitary Authority and Local Authority Districts of Great Britain.

Image: Sample from UnionMaps of varying levels of density in England and Wales

What was the impact?

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), the government department responsible for producing official statistics on trade union membership in the UK publishes Trade Union Membership annually. Most of the statistics within the publication are derived from the LFS. These statistics are used:

• in drafting advice to ministers

• in communication with the International Labour Organization (ILO)

• by the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) for research, policy development and briefing members

• by the Trades union Congress (TUC) to identify areas of low membership

The data is also represented by OECD on its labour statistics pages (alongside comparable figures for other member countries). These open data are also available (as well as other international macrodata) from the UK Data Service.

We submitted the evidence to the UK Statistics Authority with a recommendation that BEIS review how they calculate the TUM statistics.

In response, David Fry, Chief Statistician at BEIS issued the following responses:

On Trade Union Presence, we have investigated the calculation that has been used in the publication to derive this statistic, and have concluded that, as you say, the statistic does include in the population individuals who do not provide an answer to the question on whether there are people in the respondent’s place of work that are members of a trade union (TUPRES).

Having assessed these data, on balance we agree that this should be revised to exclude those who do provide an answer of ‘no’ to the question on trade union membership (UNION), but don’t provide an answer to TUPRES.

[On Trade Union Coverage] we acknowledge that we could be clearer in the statistical bulletin about what is actually being measured by this statistic, and will revise our presentation of it to make clearer that we are talking specifically about agreements between the employer and the trade union/staff association directly affecting pay and conditions.

Letter from David Fry, Chief Statistician, Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy dated 12th January 2018

Revised trade union membership statistics were published in May 2018. The following statement was included within the Technical Annex (p51). Prompted by correspondence with Rhys Davies of the Wales Institute for Social and Economic Research at Cardiff University, BEIS reconsidered the calculations used to estimate union presence in the workplace from the Labour Force Survey data.

After examining the data, on balance BEIS decided that it would be more appropriate to exclude those who did not provide a valid response to the TUPRES question from the population used to estimate union presence.

The new method excludes this group from the estimates of union presence.

Trade Union Membership 2017; Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

The change in calculating official statistics has led to an increase in the rate of union presence by 8 percentage points, roughly equivalent to 2 million employees, which should have a significant effect on policy and decision making going forward. Whilst the reporting of trade union coverage has been also been improved within official publications, questions within the LFS remain unchanged. Estimates of the collective bargaining produced by the UK Government and reproduced by the OECD will continue to underestimate the extent of union coverage in the UK.

Rhys Davies is an applied labour economist based at the Wales Institute for Social and Economic Research and Data (WISERD), Cardiff University. His research interests include the gender pay gap, work related accidents and ill-health and geographical variance in union membership.